Ponies at the Poles

By

Basha O´Reilly

Who remembers that horses helped men explore the Arctic and the Antarctic for 43 years?

Until today, the Polar “experts” have been pedestrians who do not understand the importance of horses in these regions. They mistakenly claim equines are not as robust as dogs and that there is nothing for them to eat on the snow.

But the truth is very different.

The use of horses at the Poles was started by the “father of Polar exploration”, the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen.

For the first crossing of Greenland in 1888 he improved clothing, invented a stove, introduced pemmican and recruited a horse to pull the sledge.

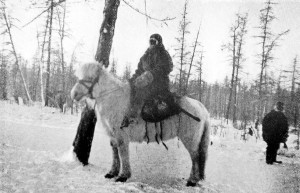

What Nansen knew was that horses could survive in freezing climates. This was proved in 1893 when the English Long Rider, Frederick Jackson, travelled 3000 miles across Siberia in winter. His sledge was pulled by Siberian horses, legendary for their resistance to the cold.

The following year, 1894, Jackson became the first to use Russian horses for polar exploration. He took four of them to Franz Joseph Land and they were a great success. They pulled 700 pound sledges along abominable tracks in temperatures of -30 F (-34 C).

Jackson noted, “The ponies proved by far the most useful animal for sledge dragging. They were hardy, and when the supply of oats and hay was exhausted, easily accustomed themselves to eating dry dog biscuit or polar bear meat.”

These lessons weren’t lost on the Americans.

In 1903 Anthony Fiala led an expedition into the Arctic Circle. He employed US cavalrymen to take care of his Siberian horses.

“The ponies were less troublesome than the dogs and more powerful, dragging loads that astonished us all,” Fiala reported.

At this point in history, horses galloped from the Arctic Circle towards the South Pole.

When the Irish explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton, left for Antarctica in 1907, he took Siberian horses, thus creating an extraordinary chain of events which led from Siberia to the Arctic Circle and then to Antarctica.

Like his Arctic predecessors, Shackleton knew there would be no grazing for his horses, so he turned to the British Army for advice. These experts knew other cultures fed their horses protein as well as fodder. To help Shackleton reach the South Pole, they invented a meat-based ration for the explorer’s horses.

Shackleton wrote, “It consisted of dried beef, carrots, milk, currents and sugar, and was chosen because it provides a large amount of nourishment with comparatively little weight.”

Shackleton had to turn back less than 90 miles from his goal but one horse, Socks, came closer to reaching the South Pole than any other equine.

The most extraordinary equestrian events happened in 1910, but they have been forgotten or misinterpreted.

Modern folklore delights in focusing on the race to the South Pole between the Norwegian Roald Amundsen and the English Captain Robert Scott.

Disregarded is the fact that Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II sent Long Rider Wilhelm Filchner to Antarctica at the same time.

Filchner had already explored Central Asia on horseback but he had no Polar experience. He travelled to London to seek advice from Sir Ernest Shackleton and Robert Scott.

Following Shackleton’s example, Scott and Filchner decided to use Manchurian horses. They also agreed to link their expeditions in Antarctica.

Scott’s last words to his German friend were, “See you at the Pole.”

The unexpected arrival of Amundsen disrupted these plans.

Scott and Filchner landed their men, dogs and horses on opposite sides of Antarctica, but never met. Scott reached the Pole but died on the return journey. Filchner was not able to travel very far inland, but he made important equestrian observations.

Filchner noticed that the dogs considered the ship as their home and had to be forcibly taken from the vessel, whereas the ponies were impatient to get to land and, “when they felt terra firma beneath their hooves, they bit, kicked and pranced from high spirits and joie de vivre.”

Filchner also noticed the ease with which his horses pulled sledges weighing 1200 pounds.

“As draught horses, the ponies have achieved miracles!”

When Filchner left Antarctica he turned his horses loose on South Georgia Island, where they thrived for many generations.

The final act in the drama of the Polar ponies took place at the other side of the planet.

In 1912, twenty-four years after Nansen left Greenland, Danish explorer Johann Koch returned there. He was determined to cross the island using Icelandic horses.

Koch’s team arrived in summer, and built a hut to pass the winter in. The temperature dropped to -50, but the cold did no harm to the horses. When they set off in March 1913, the temperature was -40.

Koch had equipped his horses with special equine snow shoes that had been used in Scandinavia for hundreds of years. His expedition travelled more than 750 miles to the west coast.

Critics argue that dogs and skis are preferable to horses. In 1930, German scientist Alfred Wegener, returned to Greenland and, for the first time in history, combined all of the innovations painfully acquired by his predecessors.

Wegener arrived in Greenland with Vigfus Sigurdsson, the equestrian expert who had served Koch. In addition to using skis and sled dogs, the experienced explorers brought 25 Icelandic ponies and equine snow shoes with them.

Wegener died in a blizzard.

That was the end of polar exploration with horses – but not the end of polar travel!

Scott and Filchner had failed to link their expeditions, but in 1951 an example of international equestrian brotherhood reached the Arctic Circle, when Donald Brown from England and Gorm Skifter from Denmark became the first modern Long Riders to journey from Hammerfest, the most northerly town in the world, to Copenhagen.

But the story of Polar ponies continues.

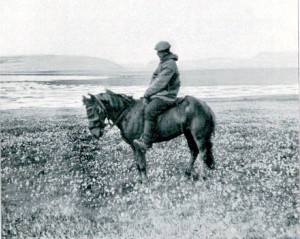

This summer a Lithuanian Long Rider, Vaidotas Digaitis, rode between his village of Laukuva to the Arctic Circle and back.

Yet what about the marvelous Siberian horses who began this story? Do they still exist?

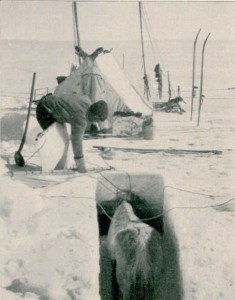

In the winter of 2004 Swedish explorer, Mikael Strandberg, set off across Siberia on skis. The Long Riders Guild had asked him to find out if the Yakut horses had survived the Soviet regime.

Strandberg made an amazing discovery. Thousands of the astonishing horses were thriving in minus 60o weather, as was the Yakut equestrian culture.

Basha O´Reilly is a horsewoman from the age of three, in 1994 Basha was Russian interpreter for a scientific expedition to Mongolia. In 1995 she rode her Cossack stallion, Count Pompeii, from Volgograd to London, becoming the only person to ride out of Russia. Thereafter she became the first woman to ride the length of the infamous Outlaw Trail from Mexico to Wyoming.

She is one of the Founders of the Long Riders’ Guild, the world’s international association of equestrian explorers and the Trustee of the Tschiffely Literary Estate, the legendary Swiss Long Rider whose equestrian journey has inspired seven generations of Long Riders.

This article first appeared in French in the excellent magazine Randonner à Cheval. http://www.randonneracheval.fr/