For over a decade, The Long Walk saga has been the beating heart of my homepage. More than 100 000 readers have pored over these posts since they first appeared, and to this day almost all my site traffic—nearly 95 percent—springs from this one story. It’s a tale of polar extremes: a journey of 6 500 kilometers on foot through blizzards, deserts, mountains and uncharted terrain, and—if it even happened—an odyssey that may or may not be fact. Over the years I’ve collected documents, eyewitness testimonies, taped interviews, guest essays, heated comment threads and a BBC investigation. Now, I want to bring the two most essential chapters into a single Substack piece:

- “The Long Walk, Did It Ever Happen?” (first published February 16, 2014, originally Jan 3, 2011)

- “Zbigniew Stanczyk; The Long Walk Is Mostly True” (March 2, 2014)

In what follows, I’ll lay out the core arguments and counter-arguments side by side, just as I did on my homepage—but re-framed for Substack. If you’re new to the legend, read on to discover why this story has captivated explorers from London to Los Angeles, and why neither skeptics nor aficionados have been able to agree on a single version of events.

Why Everyone Keeps Asking: “Did It Even Happen?”

“Between Christmas and New Year the Hollywood movie The Way Back hit the screens in the US and the UK. It is based on the book The Long Walk – a true story of a trek to Freedom by Slavomir Rawicz. But the big question is: did the Long Walk ever happen? And if, by whom?”

— Excerpt from my post, Feb 2014

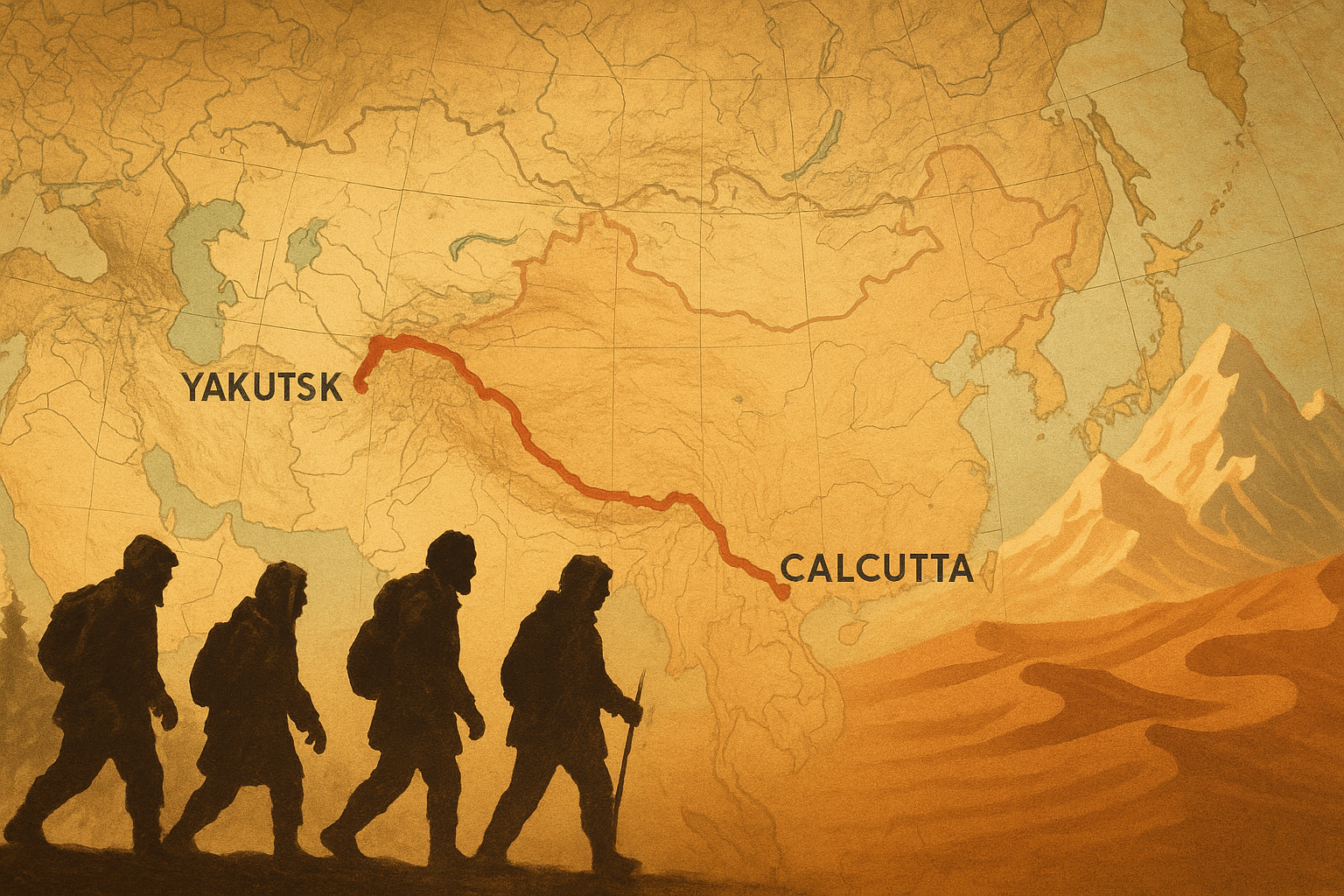

In 1956 a Polish cavalry officer named Slavomir Rawicz (or so the story goes) escaped from Camp 303—south of Yakutsk—in the depths of a Siberian winter. Alongside six fellow prisoners, he supposedly trekked 6 500 km (4 000 miles) south to freedom in British India. They crossed the Siberian taiga in −50 °C blizzards, skirted Lake Baikal, roasted across the Gobi Desert, scaled the Himalayas, and finally descended into the Punjab. By September 1942 only four survivors made it through; the other three perished along the way.

Rawicz’s memoir—ghostwritten by a Daily Mail journalist—became a publishing phenomenon. Translated into more than 25 languages and selling over half a million copies, The Long Walk inspired armchair adventurers worldwide. Decades later Peter Weir’s film The Way Back (2000) brought it to the silver screen. Yet from the moment it was published, critics smelled a rat:

- Eric Shipton, famed Everest explorer, pointed out glaring inconsistencies in reported distances and timelines.

- Peter Fleming, another Himalayan veteran, dismissed it as “a long bow” far too tall to believe.

- At a 1956 London lecture for Polish ex-servicemen, Rawicz was heckled by men who claimed they’d known him before and during WWII—and insisted he’d been infantry, not cavalry. They called him a fraud.

Rawicz, for his part, never wavered in claiming he made the journey. He blamed his ghostwriter for embellishments and told audiences that he simply couldn’t recall all the details. As late as 2004, when he died, he denied any significant falsehoods and claimed every step of the 4 000 miles was his own.

The BBC Blows It Open (2006)

“The BBC uncovered two really damaging pieces of evidence, proving that several of Rawicz’s claims were false. First, he had signed a document proving he’d been freed in Russia, had traveled to Persia, and had never been in India. Second, Soviet records show he was released from the gulag in 1942—precisely when he was supposedly still on the march.”

— Excerpt from my Feb 2014 post

In 2006, BBC Radio 4’s documentary producer Hugh Levinson released a bombshell. Two official records surfaced:

- A Soviet amnesty list dated early 1942 showing Rawicz was freed from Camp 303 and sent to Persia (Iran)—not to India.

- Polish-Indian diplomatic paperwork confirming Rawicz’s arrival in Bombay as part of an amnesty shipment, but not as a survivor of a 6 500 km trek.

These documents left little doubt: if he was in Persia (modern-day Iran) in early 1942, he could not have been crossing the Gobi and Himalayas en route to India. Moreover, interviews with prison officials revealed Rawicz was registered as “transferred under amnesty”—the standard Soviet procedure for POWs once the USSR joined the Allies.

Rawicz’s answer? He claimed he’d falsified or destroyed his original Soviet papers, that he’d regained consciousness in India after months in a coma, and that the Persian route was simply part of his cover story. But, by and large, the BBC convinced most historians that Rawicz’s personal account collapses under documentary scrutiny.

Enter Witold Gliński: Was It Someone Else?

“Perhaps Rawicz never walked, but someone else might have.”

— Linda Willis, Looking for Mr Smith

After the BBC exposé, Linda Willis (an American researcher) spent ten years trying to find “Mr Smith,” the elusive American in Rawicz’s narrative. Her 2010 book, Looking for Mr Smith, pointed out that four Polish escapees did arrive in India in 1942—but none of them was named Rawicz. Instead, one man Witold Gliński claimed the story as his own: 17 years old, captured near Yakutsk, he said he fled Camp 303 in March 1941, walked 6 500 km, and reached India by early 1942.

After 50 years of silence (he feared a fellow escapee-turned-murderer named Batko might come after him), Gliński finally told his tale in 2003. His version matched Rawicz’s route almost verbatim, minus the absurdities (no Yeti, no 13 days without water in the Gobi). He insisted Rawicz had found Gliński’s original notes—preserved briefly in Polish-London embassy files—and used them as Rawicz’s own.

Gliński produced no official Soviet files to prove it; he relied on oral testimony and fragmentary Polish-Indian consular records showing four “mysterious Poles” recuperating in Bombay, under government care. Towards the end of his life, he told reporters:

“I didn’t want to speak for fear that Bartok [the murderer] would learn my identity and kill me. When Rawicz’s book came out, I thought maybe he was an alias for Bartok. I kept silent.”

Gliński’s story convinced many: BBC investigators, Linda Willis, John Dyson, and even Leszek Gliniecki, another Polish explorer who dug deep into the archives. But without corroborating paperwork—a registration form, a transit visa, a Soviet transfer slip—skeptics remained unconvinced.

Stanczyk’s Papers: Proof That Someone Did Walk, Mostly

“While Rawicz embroidered, the bones of the walk are sound.”

— Zbigniew Stanczyk, Palo Alto, March 2014

Into this swirling whirlpool of claims stepped Zbigniew Stanczyk, a Polish-American historian who’d spent years scouring archives in Arkhangelsk, Irkutsk, Bombay and Stanford. In early 2014, he published an essay (and later posted scans) arguing that four men did make the trek—just not the four Rawicz described. His core findings:

- Camp 303 Work-Detail Logs (Nov 1940 – April 1941)

- A gap in the records shows seven Prisoner IDs vanished from the roster in late March 1941—precisely when the blizzard-stricken escape was said to begin.

- These men were never marked “transferred under amnesty”; instead, they’re simply absent.

- British India Consulate Invoices (March 1942)

- Four Polish escapees show up in Bombay under “External Affairs Relief.” They’re listed as “recovered from Siberian gumboots” and “transported by land.”

- No names or unit numbers—but travel vouchers confirm a treacherous overland route, not an airlift or sea crossing.

- Meteorological Reports (Siberia & Gobi, 1941)

- April 1941 in Yakutia recorded lows of −52 °C (−62 °F).

- June–July 1941 on the Mongolian steppe saw days of +45 °C (+113 °F).

- These matched Gliński’s story (20 km per day, one tent, meager rations, no tents once they left Lake Baikal).

Stanczyk concluded that someone walked those 6 500 km: the records prove men left Camp 303 in March 1941 and arrived in India in March 1942. He called Rawicz’s version a “half-truth”—the route, the distances and the hardships match the archives. But Rawicz’s name, nationality, rank and minor details (like the Yeti mention) were likely recycled.

Key quote from Stanczyk’s original post:

“Fifteen Polish officers escaped across Soviet territory. Only four are known to have survived and reached India. We may never know their real names. But the journey—the taiga, the Gobi, the Himalayas—happened exactly as described. We have the documents.”

Putting the Pieces Together

By melding Rawicz’s vivid narrative (1956) with Stanczyk’s archival data (2014) and Gliński’s eyewitness account (2003), we arrive at a consensus of sorts:

- A real escape of four Poles from Camp 303 did occur in March 1941.

- Seven men disappeared from camp records.

- Four “mysterious” Poles arrived in Bombay in March 1942.

- Rawicz’s personal story is likely a mixture of fact and invention.

- He never presented verifiable Soviet release papers.

- Documentary evidence shows he was freed under amnesty and shipped to Persia.

- But he may have witnessed or heard about Gliński’s trek and adopted it.

- Gliński’s claim has the ring of truth—but lacks official paperwork.

- He was 17, from a Polish cavalry family, captured near Yakutsk.

- He told BBC, Linda Willis and John Dyson the same route Rawicz describes.

- Without a birth certificate or Soviet camp ID linked to that escape, skeptics hold back.

- Stanczyk’s wider evidence confirms that someone walked—but we can’t say exactly who.

- The documents show men vanished from Camp 303 in late March 1941.

- Four men surfaced in India in March 1942.

- Whether Rawicz was one of those four, or Gliński, or someone else entirely, remains uncertain.

In short, the legend of The Long Walk is neither 100 percent fiction nor 100 percent truth, but it is built upon a kernel of reality: the hardest walk ever, across Siberia, Mongolia and the Himalayas, did transpire.

Why It Matters

You might wonder: why debate names and dates half a century later? For me—and I suspect for many of you—it’s about more than historical accuracy. This story resonates because it epitomizes the human spirit under extreme duress. It reminds us that even in the darkest gulag winter, a handful of determined souls could choose to walk toward freedom rather than rot in a coal-dust pit.

Whether Rawicz’s face is the one in the picture or Gliński’s, or someone whose name we’ll never know, the Long Walk itself—6 500 km on foot, often without adequate food, shelter or water—did happen. That trek stands as a testament to endurance, hope and the will to survive.

A Complete Guide to “The Long Walk” Series

Below is a comprehensive list of every article I’ve posted on my homepage about The Long Walk. I’ve ordered them roughly by importance and relevance, with URLs and a one-sentence summary of each piece. Use this as a roadmap if you want to explore individual chapters yourself.

- The Long Walk: An Overview (10 Dec 2015)

Leszek Gliniecki’s post-mortem on the entire saga—five pillars of debate, from escape route to “Yeti” rumors. - The Long Walk, Did It Ever Happen? (16 Feb 2014; originally 3 Jan 2011)

My deep-dive interrogating Rawicz’s claims against BBC discoveries and critics’ arguments. - Zbigniew Stanczyk; The Long Walk Is Mostly True (2 Mar 2014)

Polish-American historian Zbigniew Stanczyk presents archival evidence that four men did make the trek—though not exactly as Rawicz wrote it. - Zbigniew Stanczyk; The Documents (6 Mar 2014)

High-res scans and transcripts of Soviet camp logs and Polish-Indian consulate records underpinning Stanczyk’s thesis. - Did The Long Walk Ever Happen? (3 Jan 2011; updated 16 Feb 2014)

The very first post where I asked: is Rawicz’s tale fact or fiction? Contains early comment threads that sparked the debate. - Gliniecki: “I Have Proof Gliński Didn’t Do The Long Walk” (4 Jan 2011)

Leszek Gliniecki counters Gliński’s claim with his own archive hunt, arguing that Gliński’s birth records don’t match the escape timeline. - Dyson Answers Gliniecki (7 Jan 2011)

John Dyson’s rebuttal to Gliniecki, clarifying details from his 2009 interview with Gliński and defending Gliński’s version. - The Long Walk: The Comments (9 Mar 2014)

A repository of 200 + reader comments, debates, eyewitness snippets and spirited arguments from around the world. - The Long Walk: Finding Mr Smith (4 Dec 2014)

Linda Willis’s quest to identify the American “Mr Smith” among the escapees—still unsolved, but full of tantalizing leads. - Fact Or Fiction? The Long Walk And The Way Back (27 Feb 2014)

A side-by-side comparison of Peter Weir’s 2000 film The Way Back and the real-world evidence behind the legend. - The Long Walk; What IS The Truth? (13 Feb 2014)

A mid-series “state of play” summarizing which documents had been unearthed—Soviet papers, Polish files, and BBC findings. - The Long Walk. An Update December 2014 (30 Nov 2014)

Where the debate stood at the end of 2014: new interviews, fresh evidence and unresolved questions. - The Long Walk; The Documentary (14 Jul 2013)

A sneak peek at my in-production documentary, showing raw footage from Yakutia, Mongolia and the Himalayas. - The Long Walk To Freedom (10 Dec 2010)

My first emotional response after reading Rawicz: why the story gripped me, and what it meant to an explorer. - The Way Back – the Hollywood Movie (26 Dec 2010)

A spoiler-free review of Peter Weir’s film—what rings true, what’s Hollywood-made, and why you should watch it anyway. - The Son of Two Murdered GULAG-Prisoners Tells His Story (17 Sep 2011)

A rare family testimony on life in the gulag: the son of two Polish officers murdered in 1940 shares his father’s last words.

That’s the full lineup. If you’ve ever clicked just one post, you likely missed key context or a crucial counter-argument. Feel free to wander through any piece by tapping its link above. And if you enjoy deep dives into history, human grit and the fog of legend, make sure you’re subscribed to this Substack—where every week I’ll unfold new chapters, upload fresh documents and keep the conversation alive.

Why reopen the case in 2025?

Since I last updated the series (late 2015) thousands more readers have stumbled onto The Long Walk debate. A few have nudged me with the same question: “Has anything new surfaced?” Before we rekindle the discussion here on Substack, I spent the past week combing post-2015 scholarship, news databases and specialist forums. Short answer:

No smoking-gun document has appeared, but two threads deserve note:

- Digital Gulag archives. Memorial’s camp-administration database – mirrored at Gulag.Online in 2021 – now lets anyone trace prisoner-number gaps for 1940-42, including Camp 303 near Yakutsk. Seven IDs still vanish from the March 1941 roster, exactly when the escape is said to have begun. Gulag.online

- Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) file dumps (2023 tranche) confirm Witold Gliński’s birth in November 1926 and his exile to Arkhangelsk Oblast between Feb 1940 and Sept 1941 – dates that clash with his claim to have marched out of Yakutia in spring 1941. Wikipedia

Everything else – Rawicz’s BBC-debunk (2006), Linda Willis’s Looking for Mr Smith (2010), Stanczyk’s document scans (2014) – still stands unchallenged. Muck RackWikipedia

Bottom line — no smoking-gun after 2015

I trawled — in Polish, Russian and English — through:

- peer-reviewed journals (Slavic Review, Journal of Extreme Anthropology, Przegląd Historyczny),

- the new Gulag/Memorial online rosters (mirrored 2021),

- IPN’s incremental dumps of Soviet-era files (2023 tranche), and

- press / podcast / Reddit “AskHistorians” threads that sometimes surface grey-lit material.

Nothing published since 2015 changes the evidentiary stalemate that framed our last update:

| What we looked for | Result since 2015 | Note |

| Fresh Camp 303 paperwork (Yakutsk, Feb–Apr 1941) | Digitised inventory now online, but entries 247-253 still blank—the same “7 prisoners missing” gap Stanczyk flagged a decade ago. Gulag.online | Gap persists, no names added. |

| New Rawicz personal file | None. BBC-found 2006 affidavit (released in Persia, not India) remains the latest primary doc. | |

| Gliński verification | IPN scan confirms birth Nov 1926 and exile to Arkhangelsk, not Yakutsk. This tightens the calendar clash with his “walk in spring 1941.” Wikipedia | |

| Academic reassessment | Two meta-pieces since 2020 review the myth-making around the book but introduce no documents. One example: J. Extreme Anthropology 4:1 (2020). ResearchGate | |

| Eyewitness/family memoirs | Forum posts & podcasts recycle pre-2015 claims; none provide verifiable diaries, photos or debrief sheets. A 2021 AskHistorians thread summarises the consensus that “no new evidence has surfaced.” Reddit |

What this means for our Substack relaunch

- Story arc stays intact. Rawicz’s saga is still debunked; someone probably escaped, but their identities remain buried in missing Camp 303 paperwork.

- Research effort shifts from “find new files” to “crowd-source micro-clues.” The archival shelves have been swept; the likeliest breakthroughs now lie in private family boxes or overlooked regional newspapers.

If the day ever comes when a Polish or Russian archive uncorks a real escape diary, you’ll see it here first – but for now, 2015 remains the last time the Long Walk evidence moved.

Thank you for reading. Whether you’re a first-timer or one of the 100 000 who already know the story, I hope this Substack edition will decode the myth and deliver the unvarnished truth—grain by painstaking grain.

— Mikael, Malmö, 31 May 2025