Leszek Gliniecki’s story

I did not go to the northern reaches of European Russia by choice. I was turfed out of my home in eastern Poland, along with my family, by Soviet forces whose aim was to carve up my homeland. While the winter of early 1940 still raged, we were exiled to a special settlement in Archangelsk Province. Families were billeted in to crammed wooden barracks and food was in short supply.

I spent 18 months in exile and 9 months of them shuttling between the settlement and a nearby village school where the Soviet authorities had decreed that what I needed was an education conducted in the language of the invader that I so despised.

Even now, more than 70 years later, I still remember that school. But, to my total astonishment, one of my fellow pupils apparently did not.

The Long Walk in Readers Digest

In May 2009 I read a piece published in Readers Digest written by John Dyson which directly related to the experience of Polish exiles in Siberia and northern Russia.

The article concerned a spectacular escape from a Siberian Gulag which was chronicled by Slawomir Rawicz in his book The Long Walk. The book claims to be a true story but there have long been doubts about its veracity culminating in a BBC Radio 4 documentary in 2006 which unearthed archive material which contradicted Rawicz’s account. Although it discredited Rawicz, the investigation also raised the possibility that the escape documented in the book could have happened to someone else.

So it was something of a sensation that John Dyson said he had found someone claiming to be the true hero of The Long Walk – Witold Glinski. Dyson’s “special feature” held out prospect of significant discovery under the title: “The real long walk – Fifty years on a mystery is solved and a hero is revealed”. It detailed Glinski’s account of the escape and gave an explanation as to how Glinski’s story could have fallen into Rawicz’s hands.

The claims of Witold Glinski

The trouble was that there were aspects of Glinski’s story which I knew were not true.

The key point is this. At the time Glinski was supposed to be a 17-year-old escaping from hard labour at a Gulag he was, in fact, with me in at the Kriesty special settlement where he was attending school, aged 14. But, and this is crucial, in addition to my eyewitness account, there is readily available archive material that supports what I say.

When I wrote to Readers Digest pointing out errors in Glinski’s account compared with official documents, I enclosed copies of Polish archives but mentioned that I also had information from British archives confirming what I said.

The author John Dyson responded that he had already seen similar documentation and Glinski did not remember me. Dyson said he had seen similar documentation to the records I had sent but Glinski, who the author had found “extremely convincing”, said such information was unreliable and “fabricated”.

He had warned his readers he had no hard proof of Glinski’s claims and did not see the need for any further disclosures.

The young explorers

The Readers Digest story was followed up by media both in the UK and Poland. And in addition three young Polish explorers, who made a special trip to meet and talk to Glinski, who convinced them of the veracity of his story during a three day visit to his home in Cornwall, England.

They used the story as a rationale to recreate the escape. They wanted to spread the word that it was Witold Glinski – and not Slawomir Rawicz – who was the real hero of The Long Walk.

Their enterprise was given the honorary patronage and support of the Polish Government. They also raised sponsorship and backing from a number of leading Polish companies and organisations.

The movie

The timing of Glinski’s revelations also coincided with news that a new film inspired by The Long Walk was in the pipeline. Peter Weir, its director, re-titled it The Way Back because of his doubts about the authenticity of Rawicz’s book and has now been released.

The book by Linda Willis

Then a new development. Linda Willis, an American researcher who had found hard proof in archives to help the with the BBC expose of Rawicz, was writing a book looking into the background of The Long Walk and had done her own interviews with Glinski. It was called the “Looking For Mr Smith” – the name of one of Rawicz’s characters – and was published in November. Willis who investigates whether someone other than Rawicz had undertaken the journey reveals in the book that the she conducted interviews with Glinski in 2003 and 2006.

But so far the material I have amassed and research I have done since Glinski came into the spotlight has yet to see the light of day. I would like to present some of it now so that people can make up their own minds about his claims.

My eye witness account

My involvement in all this was initially based on the fact that the Readers Digest piece directly contradicted something I had seen with my own eyes.

I was amazed to read in the Reader’s Digest that the young teenager I was at school with in Kriesty was now being touted as the new hero of a book – which, incidentally, I had dismissed as fiction more than 20 years ago when I read it.

In the Readers Digest piece Glinski portrayed himself as the leader of the group of prisoners who broke out of the gulag just as Rawicz had done. The group included two captains and a sergeant from the Polish infantry. This is a corp of men which had long enjoyed a reputation for courage, skill and bravery, especially following the military prowess they had shown fighting for and defending Poland’s independence in 1918 and 1920. I had never been wholly convinced of Rawicz’ claim to have led these men in the way he claimed, but at least he was a 24-year-old military man – although apparently not a commissioned officer as he claimed in the book.

But the idea that men from the Polish officer corp would need to be – or allow themselves to be – led by a young teenager fresh out of school struck me as altogether beyond belief.

Our school, and Glinski’s real age

For Glinski’s story to be true he would needed to have been 17 when I knew him. That would have been impossible because only exiled boys under the age of 14 at the beginning of the school year qualified to attend classes there. Any older and they would have been sent to cut trees in surrounding forests by the Soviets.

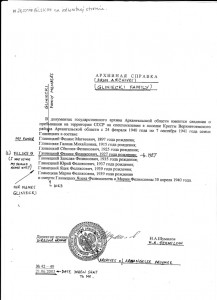

And indeed I now have three sets of archives Polish, Russian and British – where the dates confirmed what I thought. He was born 1926 and not in 1924 or any other year as he variously claimed.

I did not know him well. He and his sister Irena went to the same class – grade 5 – even though he was two years older than her. I was in grade 6 although I was younger than Glinski by one year.

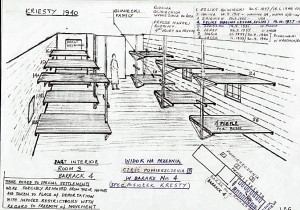

The school was situated in a single storey timber building several kilometers from the Kriesty camp. During the week, myself and six other children from exiled families shared a room in a nearby village house. The room where we slept served as an all-purpose area for cooking, eating and washing. There was a wooden table and two benches which were used for dining and homework. Glinski slept in the bed next but one away from me.

Glinski did not remember me

When I wrote to Readers Digest pointing out errors in Glinski’s account compared with official documents, I enclosed copies of Polish archives but mentioned that I also had Russian archives confirming what I said. The author John Dyson responded that he had already seen similar documentation and Glinski did not remember me.

But he added that Glinski had told him that the data was wrong in several aspects: “His age is incorrect for example, though he did not know this until he was reunited with his sister in Poland a few years ago and they discovered the records gave them birthdays only a few weeks apart.”

Glinski: records fabricated to cover foul events

Glinski apparently believed “record-keeping at that time was fabricated to cover events such as disappearances and escapes of people which could not be fully explained.”

He found Glinski “extremely convincing” despite having no hard proof of his claimed exploits – a point he had included in his story. But he added there were gaps in Glinski’s memory.

Contradictory locations and dates

During my correspondence with Dyson, Glinski made a number of contradictory claims about locations and dates. But this was the most startling to emerge: Dyson stated Glinski “worked in a gang at Kriesty preparing log-rafts for the break-up of the river ice in early spring 1941. Around February/March he went alone to Szachunia where he contacted and stayed with his father.”

Yet in the original Reader’s Digest piece Glinski was escaping from the Gulag in Yakutsk in February 1941. Szachunia is 5000 km away from Yakutsk. He could not be in both places at once. Yet, despite all my efforts to persuade him, Dyson did not see the need to publish a correction.

The upshot was that Dyson and The Readers Digest did not feel that there was any need to publish any form of correction.

Major discrepancies

There are so many contradictions between Glinski’s accounts to different people and the archives that it is hard to know where to begin. But let’s start with an extraordinary discrepancy between what he told John Dyson and Linda Willis.

Let’s start with his age. He tells Willis he was 15 in 1940 making his birth date 1925. In the Dyson piece he was 17 when in Moscow’s Lubianka prison where although no precise date is specified, it is clear that the episode happened sometime between the Russian invasion of Poland in September 1939 and his arrival near the Yakutsk Gulag in autumn 1940. This would make his date of birth either 1922 or 1923.

Readers Digest/Linda Willis: separate accounts

But the really striking thing is that in the Linda Willis story there is absolutely no mention of the Lubianka episode which was to condemn Glinski to hard labour in a Gulag. There is a fundamental contradiction between his two separate accounts of events leading up to his incarceration in the Gulag from which he later supposedly escaped.

In the Readers Digest version, much is made of a scene in Moscow’s Lubianka prison where Glinski says he was interrogated – much the way Rawicz supposedly was – then sentenced to 25 years hard labour. From there he does a few stints in work camps before arriving in Irkutsk then marching 1,800 km north east to the Gulag.

In the Willis book the Lubianka scene describing how Glinski became a convicted criminal can not possibly fit in the way that it is described in the Readers Digest.

Willis does mention that Glinski was detained and sent to an unspecified Russian prison soon after being rounded up by Russians forces when they first invaded Poland. But, crucially, Willis also says he was not sentenced to hard labour. In addition, Glinski tells her he followed his family in to exile the Arkangelsk settlement which would not have been possible if he had been a convicted criminal.

Getting to Yakutsk

So how did he end up in Yakutsk according to the account he gives to Willis? Glinski still gets to the Gulag via Irkutsk, as stated in the Readers Digest story. But this time he arrives there as a free man on a train. He ends up being taken into captivity and marched to the Gulag not because of some unstated crime punished by officials after a harsh interrogation at the Lubianka, but because the authorities simply want to “make up the numbers” of a group of prisoners who happen to be heading for Yakutsk at the time.

Glinski tells Willis that he considered that he and hundreds of other entirely innocent passengers that were rounded up and shipped to the Gulag were “fair game” because they had no travel documents.

Archives: Glinski did not arrive alone

Setting aside this massive contradiction, and now taking the Willis book in isolation, I also have serious doubts about the credibility of Glinski’s account of events.

At the start of the Russian invasion he tells Willis that, along with other students, he is rounded up, interrogated and boarded on a train destined for one of Russia’s prisons. So he is separated from other members of his family who make a direct journey to exile at Kriesty.

But he also tells Willis that although he was arrested, he was not convicted of anything and would not have to go to a hard labour camp. That meant he was later able to follow members of his family already interned at the Arkangelsk settlement which was meant for exiled Poles but was not suitable for criminals.

However, this contradicts archive information which states that Glinski arrived at the settlement at the same time as his mother, sister and younger brother and not sometime later.

Presence in a second camp makes no sense and is left unexplained

Another contradictory feature of his account concerns his claim that after Kriesty he was sent to a special settlement in Gorkowskaja Province in 1941. But this cannot fit in with information in the archives about when he was freed by the Russians and allowed to evacuate the country.

The Russians changed sides in September 1941 at which point the exiled Poles were given an amnesty. The paperwork shows Glinski’s amnesty came while he was in Kriesty. So his presence in a second camp in 1941 does not fit in and makes no sense. His reason for being there and the circumstances and timing of his departure from this camp are left completely unexplained in his account to Willis.

Leaving Russia in the wrong direction

A further anomaly concerns the way he finally chose to evacuate Russia after he was amnestied. Glinski elected to get on a train going east to Irkutsk on advice from his father.

But going east through Irkutsk out of Russia was not something which amnestied Poles would have done. It takes you in the direction of China on a route which no exile I have ever come across has claimed to have taken.

The overwhelming desire at that time was to head south to where the Polish army was forming. Polish men and teenage boys wanted to make themselves available for any effort to win back their country. But Glinski apparently went east on his father’s advice. That advice, unfortunately, was left unspecified.

Impossible timeline

Finally the one of the most unbelievable aspects of the account Glinski gives to Willis is linked with the time line implicit in his story. He was in amnestied in Kriesty in September 1941 and even claims he was somehow sent to a second camp after that. Yet he has to get to Persia by early 1942 to fit with information given in his own military records as revealed in Linda Willis’ book.

And this is where we get to the very core of this entire saga. As I’ll demonstrate later, to fit in the Long Walk within this timeframe – plus cover all the other ground he describes in his account to Willis – is absolutely impossible.

Media vs. archives

Here are some more inconsistencies between the archives and what Glinski told Dyson and Willis.

Reader’s Digest: (correspondence): Glinski left Kriesty before amnesty announced

Archives: He was at Kriesty when amnesty was announced on 2 September

Reader’s Digest: In the autumn/winter of 1940 Glinski walked from Irkutsk to Yakutsk.

Archives: He was In Kriesty between February 1940 until September 1941.

Reader’s Digest: In February 1941 Glinski escapes with 6 others from his gulag.

Archives: He is still in Kriesty 5000km away.

Willis: Glinski followed his family to a special location in Archangelsk Province

Archives: Glinski arrives at Kriesty at the same time as other family member

Willis: Glinski was 15 in 1940, hence born in 1925.

Archives: All 3 available public archives state he was borne in 1926.

The Archives Story

If Glinski is the real hero of the Long Walk he would have had to have undertaken an incredible 11 month 6,500 thousand kilometer trek from a hard labour Gulag in Siberia going south to Calcutta sometime in the early 1940s. It involves traversing a snow-swept Russia, followed by legs through Mongolia and the Gobi Desert, China, Tibet and the Himalayas into India.

But if one discounts all Glinski’s claims and recollections and simply looks at the historical documents that have come to light so far, this is the picture that emerges.

Following Russia’s invasion of eastern Poland in September 1939, Glinski was exiled to Kriesty in northern Russia in from the 24 February 1940 until 2 September 1941 when he was released with travel documents to Szachunja.

Glinski’s personal military records, as described by Linda Willis in her book, pick him up in March 1942. He was then recorded being evacuated to Persia – as it then was – with the Polish Army in April 1942.

This would leave around 7 months for him to travel from Kriesty via Szachunia south to the port of Krasnowodsk on the Caspian Sea from where Polish Army units were embarking for Pahlevi in what was then Persia.

This would fit in well with the type and duration of journey that was typically made by exiled Poles after they were amnestied and fled south from Russia joining newly formed Polish Army units on the way

But it is absolutely impossible to fit Glinski’s claimed exploits in to this allotted 7 month gap.

During this time he would have to cram in not just the 6,500 km Long Walk from a Siberian gulag to Calcutta which by itself was supposed to take 11 months. In addition there would be the time to travel 7,000 km to the gulag from Kriesty, then recuperate and plan the escape. And then there is the leg of the journey he needed to make after the Long Walk was completed. In Calcutta he would have rested then embarked on the 4,000 km journey back to the Caspian Sea. Then by boat to Pahlevi, another 200 km.

Which is more likely given what else has come to light? Glinski’s claims of a spectacular escape based on his word alone? Or did he simply evacuate Russia in a manner typical of other amnestied Poles which would fit in well with what the archives point to?

Why it matters

The story of Glinski’s supposed heroics has spread far and wide on the basis that it is somehow credible when it is not. On closer inspection there is not a shred of hard evidence to support his claims and plenty of solid evidence that he is not telling the truth. And yet there have already been consequences that deeply troubled me as Glinski’s claims gained traction in the public domain.

Following the Readers Digests “revelations”, three young Polish explorers intrinsically linked his emergence with their project to re-create the Long Walk. One of the explorers, Tomasz Grzywaczewski told the Swedish writer and explorer Mikael Strandberg on this site: “Our aim was to show that the real hero of the Great Escape was a Polish man named Witold Glinski. Not Slavomir Rawicz.”. The expedition garnered the backing of Poland’s Foreign Minister, Radoslaw Sikorski.

This troubled me deeply. I wrote an open letter to Mr Sikorski warning of the dangers of being associated – through this project – to a man whose stories did not add up. Amongst other things I was told that support for the project was justified because it helped raise the profile of the plight of Siberian exiles in the Second World War.

This is a very laudable aim and one I fully support. I, like many others who were there, feel that the plight of exiles in Siberia and northern Russia is not well known or understood. There was enormous striving and hardship. The graves of those who died thousands of kilometers away from their homeland were left overgrown and unmarked with no-one to tend and visit them. As a modest contribution, I myself provided information and plans from which our forgotten cemetery at Kriesty was located, cleared and commemorated.

But heroes need to earn their status – it’s not something that should be lightly given. There was plenty of real courage, bravery and fortitude exhibited by Poles during that period. Why allow that to be overshadowed by Glinski’s unsubstantiated tales – or Rawicz and his Long Walk fiction for that matter?

Leszek Gliniecki was born in 1927 near Grodno. This area is now part of Bialarus after parts of eastern Poland were sliced off when borders were redrawn following the Second World War. He has not seen the districts where he was born and grew up since being snatched away by the Soviets in 1939 and the new border arrangements make any such trip difficult.

His father was a forestry administrator heading up various districts in eastern Poland at a time when timber was one of Poland’s leading economic activities.

In October 1939 he and his family were turfed out from their home by the Soviets, and on the 10th Feb.1940 forcefully exiled to a special settlement called Kriesty in Archangelsk Province of northern Russia.

Over the last 20 years he has been collating historical maps of Russia and researching other information in order to get a better understanding of his family’s movements and experiences during and following exile.

Three and a half years ago he instigated a project to find and re-establish the cemetery in Kriesty where – amongst many others – two infants in his family were buried shortly after being exiled to the camp in February 1941.

He researched archive information to locate Kriesty which no longer appears on modern maps. He also made sketches and plans based on his memories of the camp that proved crucial in locating the cemetery which had long since become an indistinct area of scrub and woodland. It has now been cleared and enclosed.

He has friends among local Russian people who, along with local schoolchildren, helped out with the project. Many of their families were internally exiled to the area by the Soviet authorities.

He also researched archives information to provide information for a commemorative plate, unveiled earlier this year, which remembers all the names of those who died in Kriesty – thousands of kilometers away from their homeland.

Leszek Gliniecki is retired and living in London, England.

Mysterious group of Polish escapees in India.

In March 1942, Chief Secretary to the Government of Bombay, Political and Services Departments, H.K. Kirpalani reported to the Consul General of Poland in Bombay about the arrival of a group of four Polish men who claimed to have escaped from the Soviet Gulag. They had crossed thousands of miles and were taken care of by the Government of India External Affairs Department. Four men recuperated for weeks in the local hospitals as per receipts from the Salvation Army and other facilities. Local government submitted expenses for their stay to the Polish diplomatic outpost. These records can be found among the accounting records of the Polish Bombay Consulate General, to the best of our knowledge, the only documentation from that Consulate which survived World War 2 (Poland. Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych, Hoover Institution, Stanford University).

We assume that the main body of the Consulate’s documentation was destroyed by the Polish diplomats after the British government withdrew recognition of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London in 1945.

We don’t know much about the fate of these men after April 1942, whether they returned to Europe or joined the Polish Army in the Middle East which left the Soviet territory after the summer of the same year.

Among the accounting records there are several “Certificates of Posting” from March 1942 about the heavy exchange of mail between the Polish diplomatic outposts in India and the Deputy Commissioner of Police Security Control in Calcutta and the Undersecretary to the Government of India Home Department in New Delhi. The content of this correspondence must have been destroyed.

Escapes of the Polish officers from Soviet Gulag

State Archives of the Russian Republic, (call number: GARF, f. 9401. op. 2, d. 173, l. 125-126), contain a report from November 1, 1945 by the commander of the 2-nd division of GUPVI NKVD SSSR , Major Bronnikov, who states that out of close to 100,000 Polish Army soldiers handled by the Soviet authorities between 1939 and 1941, approximately 1,082 Polish officers escaped from the camps.

Camp commanders frequently falsified reports on the circumstances of disappearance of the prisoners and even if the number wasn’t this high, we can assume that several hundred must have attempted the escape. A small percentage of them survived the Siberian ordeal. There are numerous reports in the General Anders Papers stored at Stanford University confirming these escapes. Anders collected testimonies from Poles who successfully reached the gathering points for the deportees on Soviet territory before he took that remarkable Army to the Middle East in 1942.

What makes Bronnikov’s report look reliable is that it officially admits to killing, by NKVD, 15,131 Polish officers. This fact remained a Soviet/Russian state secret until the mid 1990?s and the document couldn’t be made public until the time of official inquiries about the Katyn Massacre.

Could Mr. Leszek Gliniecki explain where he obtained the documents he is quoting on this web site? Some of his conclusions are incorrect.

Zbigniew L. Stanczyk, Palo Alto, California

Thank you for allowing me to comment on Zbigniew L. Stanczyk’s submission.

Firstly, I have never claimed to have evidence that no Polish officers ever escaped from a Russian Gulag and subsequently made their way to India by some means.

The evidence I have obtained is specifically related to Witold Glinski. It overwhelmingly points to the fact that he did not make the Long Walk as he has claimed.

With this in mind, I would like to review the information provided by Mr Stanczyk and compare it with the archive evidence which I have obtained pertaining to Witold Glinski’s claims.

Mr Stanczyk speaks of a report of four Polish men appearing in March 1942 in India – but this does not fit into Glinski’s story.Yes, Glinski claimed he was one of four escapees, but only one – Glinski himself – was a Pole. The others, according to Glinski’s account,:were Mr.Smith — an American plus one Serb and one Ukrainian.

Let’s return to that key date when Mr Stanczyk says the escapees appeared – March 1942.

Witold Glinski – according to his military records from the British Ministry of Defence (Polish Section) – joined the 8th Infantry Division of the Polish Army on the 7th March 1942. And also, the records say that he was evacuated to Iran (Persia), where on the 1st April 1942 he came under British Command.

I’ve also discovered some further archive information that directly contradicts Glinski’s claim to have joined the newly formed Polish Army after his supposed Long Walk to Calcutta. To fit in with archive material – which I will outline shortly – Glinski would have had to have returned to Russia in order to join the Polish Army on the date which is specified on his military records. This makes no sense at all.

Archives at the Institute of Sikorski say that Glinski’s division – the 8th Infantry Division – was placed in the north of Tashkent in Russia on the 7th March 1942 – the date that he joined. The archives state that that Division was then evacuated via the Caspian Sea, on the 30th March 1942, to Pahlevi (in what was then called Persia).

Additionally, a historical research publication entitled “Polish Embassy in Russia – years 1941 – 43? — confirms that the 8th Infantry Division was stationed North of Tashkent, and that on the 19th March 1942 General Anders decreed that the 8th, 9th and 10th Infantry Divisions would leave Russia. The evacuation of all three divisions was completed by the 3rd April 1942.

This is very important additional information which has not come to light before in relation to Glinski’s claims. Because if he really had walked to India, Glinski would have had to cross back into Russia at some point in order to be able to join the army unit which his records clearly state he was part of!

Glinski’s only account of how he came to join the Polish Army after leaving Calcutta (to Linda Willis) states catagorically that he arrived in Pahlevi via the Persian side of the Caspian Sea. There is no mention of returning to Russia and indeed returning to Russia would not have made any sense at all.

Returning to Mr Stanczyk’s information, I would be very interested to see copies of the Indian receipts from the Salvation Army which still apparently exist, and from the other facilities.

This would be of historical importance. It would give a good idea of the condition of the escapees, and perhaps of their recuperation time, and even more important, the location of the hospital and the facilities. This generally would add considerably to the knowledge of what was happening during those years.

With kind regards.

Leszek Gliniecki.

Thank you Mr. Stanczyk for the very interesting information. Will these findings be published in a more detailed way that we can look forward to?

JMasefield

A reader made me aware of this new book called Against Destiny by Alexander Dolinin, see http://www.againstdestiny.com/

I am about to give a eulogy at my father’s funeral and am wondering where I can get archives from. I know he lived in Eastern Poland up until 1939 and was released from Siberia in August 1941. His name used in Poland was Pawel Drozdowicz, but to secure release he changed it to Pawel Drozdowski. His real DOB is 08-10-23 but gave 08-10-24 so as to avoid conscription into the Russian army. I really need to know where to gain info as to his internment into a Gulag or camp and am not sure how long he served. As a child I recall him claiming to have been amongst those written about in the book “The Long Walk” I have since dismissed this as I have seen a record form the English Army that he was released from Russian prisoner of war camps around the end of August 1941 under the Sikorsky-Stalin agreement which appears to be the same reason why Slawomir Rawicz could not have escaped as you can’t have records of release in addition to escaping. I am eager to know when and where my father spent time in Siberia and perhaps why he was sent there from Luboml in Eastern Poland (Which is now Ukraine) Please can anyone let me kow where is best to go for this. Thank you in advance regards Andy

Andrew, have you tried IPN – Instytut Pami?ci Narodowej?

http://www.ipn.gov.pl/

Please accept my condolences on your farther’s death.

And good luck in your search.

Andrew Drozdowski.

Further to your letter, you should also try organisation Memorial, they may have information you are searching for.

e-mail address— info@memo.ru

I wish you success.

My condolences on your father’s death.

Hi all of you,

A reader just sent me this:

Mikael,

You may want to post the following two links on your website. In them Peter Weir discusses The Way Back and presents his side of the historical veracity question.

Part 1:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJz9PeAXsFE&feature=relmfu

Part 2)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZR-Cr4OZ2Z4&feature=relmfu

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I have followed the latest twists of the Long Walk/Way Back story with a certain interest, and appreciate the fundamental research by Mr Giniecki!

In April 2006, the Swedish Populär Historia (printrun 30 000 copies) had a story and an advertisement for a new edition of Slavomir Rawicz’s story, just out from the Historiska Media publishing company, with the title “The escape from Stalin’s camp”. It was prefaced by one Swedish radio correspondent who ascertained that it was indeed a true story.

After reading only the first three-four chapters, it was evident that this story had no relation to Soviet camp realities, nor to the NKVD interrogation methods. While in Moscow in May-June 2006 (for another historical research project) I questioned the best experts at the GARF Russian state archive and RGVA state military archive; both for any indication of the individual in question, and for details on escapes from the Gulag.

By 1940, and this is the number one crucial issue that shipwrecks Rawicz story, no sentences of 25 years were given to any political (or criminal) prisoners. The maximums were either 10 years or a death sentence. the 25-year-camp-sentence was introduced in the Criminal code during the German-Soviet war only.

There never was any Gulag camp no 303, nor in Siberia nor anywhere else. Such a number was given, much later to a POW camp in the vicinity of Moscow.

It was unlikely that any “small fish” like Rawicz would have a several-day hearing before his sentence was read by the judge.

While in Moscow in 2006, I got in contact with the BBC team and we exchanged some ideas on this “The Long Walk” background. I was from the start sceptical, whereas they had an open agenda. More and more information in Autumn 2006 confirmed our doubts. I published an article on this subject in the Swedish “Historisk tidskrift” in 2007. It has be carefully translated into Russian (see links below).

http://www.historisktidskrift.se/fulltext/2007-2/pdf/HT_2007_2_269-278_samuelson.pdf

http://scepsis.ru/library/id_2321.html

I hope that any Google translations of this texts will reflect the substance matter of my article!!

In my article, I inter alia compare the descriptions of Soviet, and NKVD, realities given by the economist Stanislaw Swianiewicz “In the Shadow of Katyn”. I then wrote, and still consider that it would be much better to base a film on his experience than on the pure inventions concocted during the Cold war in Great Britain.

I say this even after I have seen the Peter Weir movie that premiered here in Sweden last Friday.

Lennart Samuelson

A reader send me a link that one of the advisers of the film The Way Back was indeed the distinguished scholar Zbigniew Stanczyk who asks Leszeks Gliniecki to verify his claims above here, see http://www.linkedin.com/pub/zbigniew-stanczyk/10/82b/795 I will write to Zbigniew and ask if he can write an article. It would be extremely good to hear what he makes of it all. Everyone I have asked, involved in it all, except Peter Weir and Annie Applebaum have commented on the issue. It would be very interesting to read about their opinions, especially Annie’s, since her Gulag book is just amazing. Still trying. M

The Polish daily ‘Gazeta Wyborcza’ ran a story on 15 April http://wyborcza.pl/1,75478,9435847,Ucieczka_prawdziwych_niepokonanych.html

about two Poles, Olgierd Sto?yhwo and Adam Backer, who escaped from Russia to Iran in 1940 (i.e. before the Anders-led exodus) and then via Afghanistan to India. The author of the article believes this may be the real story behind the ‘Long Walk’.

In the article, Rafa? Zasu? describes how, when they reached India, Stolyhowo and Backer became a ‘local sensation’ and were written about in the press; the Associated Press of India Correspondent for some reason mistakenly gave the number of escapees as four!

Anyway, it’s an interesting article and adds another piece to the jigsaw puzzle…

One of Zasun’s sources is the Sikorski Institute in London. I’m not sure where else he got his information from. If I have a bit more time and anyone’s interested I can try and translate some of it and post it here.

Regarding George Lisowski posting.

In order to cross from Soviet Union to India in 1940’s required only to traverse about 15-20km of Afghanistan territory, therefore it not represented a great problem, except for the avoidance of the border guards. At that time Pakistan did not yet exist.

With reference to Lennart Samelsson earlier posting.

I have read with interest Lennard Samuelsson article “Escape from the Gulag, or a prisoner of the myths of the Cold War?” as translated by Anastasia Kuzina, although the article deals mainly with Slavomir Rawicz, it was interesting to see his comments on the book “Gulag” by Anne Applebaum, and the attitute of Per Urvegord.

I agree that it is difficult for some people to accept the truth of some events if their minds are already, and unequivocally, made decision to the contrary.

It was perhaps was fortunate that in the case of Slavomir Rawicz the relevant documentation has been found, although rather late, and the deception has unrolled, otherwise controversy would have continued with no end to it.

In the case of Witold Glinski documentation was easily available for those who wanted, and were willing to consult it,and for those whose duty was to consult it before embarking upon costly, and financed by others, expedition.

Witold Glinski — Short summary.

For those who are new to these pages, and for better understanding, and perhaps to facilitate navigate through all the information, the following is a brief summary of Witold Glinski’s exile in Russia during 1940-1942.

Three versions as presented by John Dyson.

Version number 1. — In May 2009 issue of Reader’s Digest:

17 year old Witold Glinski, early in 1940, is sentenced in Lubianka Prison to 25 years of hard labour.

He arrives to a gulag, near Yakutsk in December 1940, from where he escapes in February 1941, and reaches India in January 1942.

Version number 2. — June 2009, in correspondence with Leszek Gliniecki John Dyson agrees Glinski’s presence in Kriesty settlement, in Arkhagelsk Province of Russia, in February and early Spring of 1941.

The above automatically precludes his presence in Yakutsk (4500km + from Kriesty),. or Lubianka — sentenced people would not be allowed to be in Kriesty,.

Additionally, Glinski somehow travels twice, from Kriesty to 700km+ distant Szachunia, to see his father. (Under no circumstances this would have been possible).

Version number 3. — Posted by Dyson on the internet on 7th January 2011.

According to this version Witold Glinski is more or less allowed to do what he wishes while in exile. He settles his mother in some village, visits his father, who is now in a near proximity of Kriesty, and then he decides to escape. The time frame varies from the previous versions.

The above three versions are diametrically opposed to each other, and therefore none can be taken seriously. It need to be added that each of these versions, according to John Dyson, was compiled from the notes taken by him during his 8- day interview with Glinski in November 2008.

However the first of those versions became rationale for Tomasz Grzywaczewski, and others, to undertake Expedition in the steps of Witold Glinski, and to this day Tomasz Grzywaczewski with companions propagates the first version as a true historical event.

Linda Willis and her book “Looking for Mr.Smith” published in November 2010.

I must complement Linda Willis for her perseverance in pursuing the subject, and also in rejecting version given to her by Glinski on the manner he arrived to Yakutsk.

Incredulity however arises, why did Linda Willis accept his version of the actual escape, while rejecting first part as not credible, particularly when the time frame did not allow for the long walk to take place.

However I must thank Linda in providing the name of the military unit, which Glinski has joined on the 7th March 1942. (given in the archives).

The following is therefore Witold Glinski’s history in exile in Russia.

1. 10th February 1940: forcefully sent into exile.

2. 24th February 1940 arrives to Kriesty in Arkhangelsk Province of Russia. (location of his exile).

3. Amnesty announced for Polish exiles in August 1941..

2nd September 1941 Glinski receives documentation allowing him to leave Kriesty for Szachunia, Province Gorki, to join his father.

4. 7th March 1942 — Glinski joins 8th Infantry Division of Polish Army in Czok-Pak, Russia.

5. 1st April 1942 — 8th Infantry Division arrives to Pahlevi in Persia, and comes under British Command.

The above is based on the archives from:

. Polish Remembrance Institute in Warsaw.

Arkhangelsk Province Internal Affairs Department.

Polish Army in the West (London), and extract quoted in Linda Willis’s book “Looking for Mr.Smith”.

Gen. Sikorski archives in London.

Polish Embassy in USSR years 1941-1943.

. But even more important, as far as I am concerned, was my personal knowledge that Witold Glinski lived in the same room as myself between September 1940 and June 1941 while we were attending the same school in Russia during our exile.

There was no possibility that he could have been escaping from somewhere else during that period.

Great research, information, and article. Thanks for putting so much work into it and making it available online!

Hi George Lisowski!

I read your comment and would love to have a translation of the article you talk about! Thank you for spending the time to do this if you can afford it! 😀

Thank you also to Leszek Gliniecki for your great article research and particularly for the work you have done for all the people that where at the Kriesty camp! People who have suffered so much undeservedly should indeed at least be honoured and remembered!

Thank you!

Claire

Uccle, Belgium

Hi Claire Meunier,

I’ve written to Gazeta Wyborcza to ask if I can translate the article and am waiting for the answer.

best

George

With regard to Claire Meunier and George Lisowski’s recent postings on the Gazeta Wyborcza article, please be advised that while a polished translation by someone knowledgeable in both languages often is preferable, anyone can now generate their own translations from one major language into another by means of such online translation facilities as Google Translate or Yahoo Babel Fish. While quality varies, generally these free utilities can produce reasonable output, especially for discursive text such as a newspaper report.

Hi,

Gazeta Wyborcza never wrote back to me – perhaps my email never got through to the right person.

However, there is also a wikipedia article about Olgierd Stolyhwo in Polish here http://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olgierd_Sto%C5%82yhwo which I translated into English and left on their helpdesk board, if they decide they want to use it http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Help_desk/Archives/2011_October_25#Translating_a_Polish_Wikipedia_article_into_English

Claire Meunier, Uccle Belgium.

Further to your posting of the 18th September re:Kriesty.

On the 1st December there was an article in a Polish newspaper published in England, Dziennik Polski, by Leszek Gliniecki, on the subject of the only one of the type in Russia, Rememrance Monument/Plate that has been erected at the Kriesty cemetery.

The Ceremony took place on the 30th October in the presence of many dignitaries and television, and speeches.

The article is in polish, traslation by Google is, unfortunately, not always reliable.

Hope that this may me of interest to you.

My Grandfather Zdzislaw Piwowarski, one of the Poles who did walk to India.

I can tell you the story is 100% true. I have a full acount of the trip from my Grandfather. He wrote the account and his wife (Margaret) typed it up for him. I quizzed my Grandfather about his trip and just did not realise until the film appeared that information out there was so scant.

As proof, I honestly have the passport that he was issued in Bombay. I also have his Virtuit Medal. etc etc.

My Grandfather was my hero, I have only recently come to realise that he may be a true hero..but he would never have liked that.

Sorry I really should qualify my comments. I am 100% certain my Grandfather was put in a Gulag in Siberia. I am certain he walked to India. His story is true. The Story of the book and film I have no idea if this is true or not. However the parallels to my Grandfathers story and the documents I have such as his passport issued in India tell me there is more to this. I notice also the the team doing filming were keen to trace my Grandfather or family (me). I know my Grandfather’s story well but I am really keen to find out how this team locked onto him.

I can’t comment about the fact that who really did the walk.

But I was moved when I saw the movie by Peter Weir.

The story is incredible .

Leszek Gliniecki , был инициатором установки памятной плиты на кладбище посёлка Кресты (современное название Сосновый). Памятная плита действительно была установлена в указанное время, где и стоит до сих пор.

initiated the installation plaque in the cemetery of the village crosses (now Pine). Truly memorable plate was installed at the specified time, where and still stands today.

Cnacuбo Oлeг.

Thank you Oleg.

Oleg’s posting refers to the unique Monument/Memorial Plate which was erected at the Kriesty cemetery, where we were forcibly exiled in February 1940.

The above Monument/Memorial Plate was ceremonially unveiled, in the presence of high Polish and Russian personalities, on the 30th October 2010, the day set aside in Russia to commemorate victims of the Stalinist regime.

Perhaps it is worth to mention, because Oleg refers in his posting, that I was the initiator to have such a Monument/Commemorative Plate erected, and that the wording was in accordance with my text, with the exception that my name was included afterwards.

It is Unique in the sense that it is the only Monument/Commemorative Plate erected on a Polish Special Settlement cemetery in Russia, which enumerates the names of all those buried there with their year of birth, and the date of death stated in Polish and Russian, which I produced for that purpose.

Returning to the subject of Witold Glinski and The Long Walk, it may be of interest to state that in 2008 Dissertation by Alyona Kobzap “Polish Exile” includes the name of Glinski and his sister Irena. This information was supplied by me in 2007, that they lived in the same room as myself while attending attending a Russian school.

In order to attend the school Glinski had to be under 14 years old in September 1940. This confirms his age, and also information in all the archives, and also mine, that Glinski was born in 1926 (November 22), this also appeared later in John Dyson’s Internet Posting of the 7th January 2011.

My above information about Glinski was sent to Russia almost two full years before anybody has heard about Witold Glinski, and also before John Dyson’s article appeared in the Reader’s Digest.

Does anyone know who the American, Mr. Smith, was? Both Glinski and Rawisz mention him. Did they both read about him from yet a third account of such a journey?

To all who have contributed comments:

I saw the movie and then read the book by Slavomir Rawicz. Like others I was greatly moved by the story.

I wonder whether any of you have noted how similar the story is to that of the hero archetype in literature who is on a great quest, is tested time after time, narrowly escaping death, and is eventually successful. I wonder if that aspect of the book originated with Mr. Rawicz or was introduced as part of the embellishment of the ghost writer. Perhaps some of the skepticism is related to that aspect of the book.

I mention this because I am wondering whether the controversy is a question of who accomplished this great escape or a question as to whether this escape actually happened.

In any case, I am greatly moved by the heroic response of the Polish people to the inhuman treatment they received at the hands of the Soviets as well as the Nazis. I believe that the strong will and determination of the Poles during this time would have spawned some (many?) Poles who could have and did carry out deeds such as this near superhuman escape. But even if the escape didn’t happen exactly as described, the fact that it seems credible — that maybe it really did happen that way! — is testament to how widespread is the knowledge of the great courage of the Polish people during the war.

My father was born in Poland 80 years ago,his name is Basil Glinski, I do not know much about his life as a kid inPoland, he is now 80 he mentioned he was born in a town called Pinsk not sure spelling. He then mentioned that he was in some camp as a youngboy when one night he was taken from his parents by the guards and sent away and eventually after a long period a group of kids ended up in Capetown South Africa,where we still live today, he made mention that his father was some how involved in Forestry. What I am asking for please is someone to advise me as to how I can track my dads history,I would not know how to start. Due to all his hardships as a young boy my father was reluctant to discuss his past. Oh he always claimed to be of royal descent (sure this was a joke) he has never spoken to another family member of his since he was removed from his parents that night. Any. Advice input would be appreciate . Regards Mark Glinski

Helo Mark Glinski

on related subject: There was a refuge camp for Polish Children evacuated from the War zone of Poland in Sept 1939 located at OUDTSHOORN South Africa. Some 5 000 children were there at some point, Consult the web site for Oudtshoorn —very limited info..

I spend Dec/Jan at my son’s ((Stephan) in Stellenbosch hence the interest, planning to drive there one day.\

regards

further” look up

http://feefhs.org/links/poland/orphan/polorf-a.html

you Father’s name seems to be on the list of the children —born 1933 in Pinsk

Thank you for your input

I know nothing about Glinski but my father was a 12 year old boy who escaped the Soviet camp leaving his mother and sister and travelling alone ended up in Palestine joining the Junaki. It may have taken him more than a year, I’m not sure. He found his mother 10 years later living in Canada. He is dead now and I only have bits and pieces of his story. I wish he had told me the whole story but it was too difficult for him…

In 2006 it was a SHOCKING revelation to hear my hero, Slav was a LIAR. Now it is but just a bland, flat fact to be considered before moving onto the next phases for me : Linda Willis’ book, Peter Weir’s fictional movie and Witold Glinski’s controversial tale. The Long Walk meant so much to me for 18 years but that Radio 4 programme… We all have those moments don’t we?

My Grandfather was a Polish Cavalry Officer during the second World war. As a child I would occasionally hear how he had been capture by the Russians and to Russia. I remember his story of escaping Russia the being captured by the Nazis only to escape and make it to England.

It has long been a story that I believed.

After reading this I have decided to get copies of his War Service records in the UK.

I will update this page when I have them and whether his story is in fact true.

The Long Walk” in the footsteps of Witold Glinski.

2nd version as the result of June 2009 correspondence with Leszek Gliniecki, who also was, and knew Witold Glinski at Kriesty, and pointed out to John Dyson inconsistencies between archives and the above version with enclosed copies of the archives as confirmation.

Hi Mikael, I think that it will be beneficial to place the following article on the page – Gliniecki: I have solid evidence that….

It appears to me that the new readers that become interested in the subject of the Long Walk and Witold Glinski’s participation in it will benefit from a summary which will allow them to more easily navigate through over seventy earlier postings.

I shall start the first part with the evidence from Polish , Russian and the Polish Army in the West archives.

1. Witold Glinski was born in 1926. (all three archives confirm this).

2. Witold Glinski, together with his family arrives at the special settlement Kriesty, in the Arkhangel Province of Russia, on the 24-th February 1940. (Polish and Russian archives confirm this, Army archives not involved).

3. Witold Glinski, and his family are amnestied in August 1941, and on the 2-nd September 1941 receive documentation allowing them to travel to their chosen destination, 700km away in Szachunia in Gorki Province. (Polish and Russian archives,. Army archives not involved).

John Dyson’s versions based on the 8-day interview with Witold Glinski (WG) in October 2008 are as follows

1st version as published in the May 2009 Reader’s Digest.

1. 17 y.o. Witold Glinski finds himself in Lubianka prison at the end of 1939, or early 1940, hence born in 1922, and is sentenced to 25 years of hard labour.

2. In December 1940, during most severe winter on record, Glinski arrives to a Gulag somewhere near Yakutsk.

3. In February 1940, Gliniski with three Polish Infantry Officers, a Mr.Smith, and two others escapes from the Gulag.

4. In January 1942, after eleven months 6500km walk, he arrives in India, without the three Polish Officers who have perished on the way.

Note. This version became the rationale for Tomasz Grzywaczewski, and others, to undertake an expedition “

1. John Dyson acknowledges that Witold Glinski was at Kriesty, and additionally states that in February, and early Spring 1941,Glinski has apparently travelled three times in February 1941 between Kriesty and Szachunia, where his father was, a distance of 700km each time. This would have been impossible, firstly, because of the winter conditions, and secondly because the exile conditions imposed on us regarding freedom of movement that would not allow anything of that manner to take place.

2. No response was received regarding Glinski’s age, or the contradiction with the archive evidence (and my own eyewitness account) that Glinski was at Kresty during 1940, not Yakutsk Gulag 4500km away.

3. Reader’s Digest terminated the discussion, hence no resolution of this problem.