Sahara…listen to the word…it is best pronounced when in the Great Desert itself, when a visitor tries to take a breath in the most demanding of heat…it will than be said properly Sahra! My first visit, on a bicycle, crossing it from north to South, back in 1988, are some of the most memorable days of my life. Six hot, but enthralling months of my life made me forever love the smell of the desert, the people and the great sense of freedom experienced. I am therefore, extremely honored and happy to share this article by the arabist Eamonn Gearon with you and I look forward to reading his book about one of the most spiritual places on earth – the Sahara!

The Sahara: A Long Way Away from a Cultural Desert

by

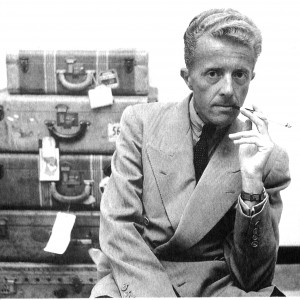

Eamonn Gearon

In keeping with anyone blessed with an active imagination, as extensive as my wanderings through the Sahara have been, they are nothing compared to my mental journeys through the Great Desert. The greatest journeys are not always physical, and one can be transported just as easily in an armchair as on a camel.

I was a child the first time I entered the Sahara, sitting on my father’s knee. We were at home in Wiltshire, that fat, green English county best known as the home of Stonehenge. Beethoven’s 6th Symphony, the Pastoral, was on the record player. My father always played Beethoven when he remembered Egypt in the 1950s.

Although he was there in an official, military capacity – something to do with a canal by the name of Suez – his memories of that country and its people were fond ones, and invariably revolved around the desert.

If this reminiscing seems a long way from the Sahara, it both is and is not. Even unremembered, unremarkable incidents in one’s childhood can have a profound impact on the rest of his or her life.

There is no doubt that I have spent the past two decades in the Greater Middle East because of my father’s tales of a far away country he loved, even if, unsurprisingly, this love was not always equal on the part of the Egyptians.

When I started reading about the Sahara for myself, the first thing that struck me was its scale and its seeming emptiness. A part of the earth roughly the size as the entire United States of America, but with a population of approximately 3 million.

Once these figures had been absorbed, it was not the limited numbers of people that impressed me so much as the fact that the desert was not empty. It was, and always has been, home to a diverse number of peoples, both locals and foreigners.

I next understood that the Sahara had not always been a desert, but was once an ocean, and later variously forests and pastures; that “Sahara” simply means “desert” in Arabic; and that the human records of life in the Great Desert, its cultural history, are as many and varied as the flora and fauna one finds there.

Indeed, the landscapes of the imagination are far more numerous than the various physical landscapes one finds there.

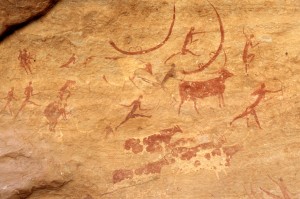

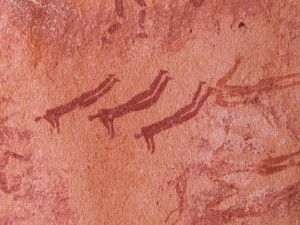

The earliest extent records are those rock paintings and carvings found across today’s desert. These global treasures hold out the promise of great insight into our Saharan-dwelling forefathers, and yet they are frustratingly among the least understood human records, and most open to fantastical interpretations.

Hunting scenes are fairly easy to interpret. Recognisably male figures carrying spears and chasing four-legged animals with horns do not require the observer to have a degree in archaeology or art history. Other images are less straightforward. People swimming? Big cats dancing?

Did the “round-headed” figures come down from outer space? What do you think?

And while men apparently copulating with elephants and rhinoceros might just be examples of prehistoric lavatorial, schoolboy humour, they could easily have another, deeper meaning: we simply do not know.

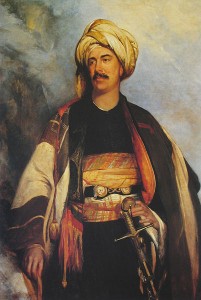

Rushing forward thousands of years, the artistic records created by European artists who have been ‘discovering’ the Sahara since the late Eighteenth century were created in the same environment. In response to an encounter with their surroundings, the artists were impelled to create, to leave behind some record of a moment in time or a day in the life. They are all saying, “We were here, this is who we were, what we did and what we found.”

Fromentin declared that he only fully came alive in the Sahara, and that the intensity of these feelings grew the further south he travelled into it, while Paul Klee announced that it was the influence of being under North African skies, and the intensity of the light there, that he became an artist.

The paintings of David Roberts, who travelled through Egypt and the Levant in the 1830s, became the virtually canonical interpretation of the East for close to one hundred years.

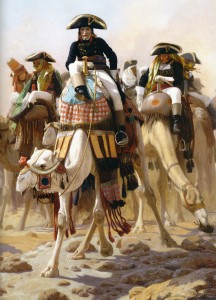

Roberts’ time in the region was inspired in turn by a far less pacific visitor to Egypt. On Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, he was accompanied by two armies: one of soldiers, the other of scholars. These savants were responsible for exposing Europeans to a world they had more or less ignored for centuries. Perhaps this was no bad thing.

Napoleon’s short, inconclusive invasion marked the start of the last great scramble for the Sahara. By 1900, of the 11 modern nations that now make up the Sahara, only Libya remained independent. This too fell after the Italians invaded, snapping up the last slice of independent North Africa in 1911.

But these European invaders were just the last in a millennia-long line of like-motivated imperialists, which included the Greeks, Romans, and Vandals. Non-European invaders included the Phoenicians, Persians and, of course, the Arabs.

It was the invasions by this last group that most permanently changed the cultural face of the Sahara and its people. The eventual imposition, or adoption, of Arabic as the language of commerce, government and worship is the most obvious changes in local circumstances. The spread of Islam, which utterly replaced older, indigenous faith systems, was the most important reason for this.

Returning to the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries, this was not just the era of European expansion and domination of the Sahara, it was also the period that saw the proliferation of portrayals of the Great Desert. The artists we mentioned above; these were soon followed by poets and writers of prose.

In the same way that Roberts dominated Nineteenth century painterly portrayals of the desert, so Beau Geste and the French Foreign Legion loom large on the early Twentieth century literary landscape. A kepi-clad bugler and a deserted fort was, for decades, all that most people knew about the Sahara, or cared to.

With the dawn of cinema, the literary visions were added to and exploited mercilessly by filmmakers who understood the instinctive attraction of a shot of sand dunes stretching as far as the eye could see.

One of the best-known writers on the Sahara, Paul Bowles of “The Sheltering Sky” fame, very publicly announced that he wished the film of his novel had never been made. Others were less chary.

And in spite of the critics, famous and anonymous, the Sahara continues to attract visitors; to awe strangers and residents; to prove most alluring when revealing itself to those who have the desire to know it, over time.

For my own part, the journey that began on my father’s knee reached fruition 20 years later, when I first entered the Sahara. And now, after nearly another two decades, I am delighted to have sanctified my love for the world’s greatest desert in my book.

The Sahara in which I roamed, first with the Bedu and later alone, but in the company of my camels – Osama, Ibn Kelb, and Baby – was physically demanding. The journeys were tough. They built character and left scars. Today, I look back on those sacred days and nights with love without compare.

Whilst resident of the oasis of Siwa, Egypt, recovering from amoebic dysentery after one of my more adventurous travails, I met my now wife. Such a priceless find, in the midst of the seeming wasteland, daily reminds me of the importance of the Sahara in my life. In this world, it pays to be alive to both one’s physical and imaginary landscapes.

Eamonn Gearon is an Arabist, analyst and author who has lived and worked in the Greater Middle East – from Kabul to Casablanca – for the past twenty years.

Eamonn’s life in the region started in the Sahara, where he lived and travelled with the Bedu, learning a vast amount of desert lore from them before engaging on a number of lengthy solo, camel-powered expeditions in the Great Desert.

His book “The Sahara: A Cultural History” came out in the UK in June 2011 (Signal Books), and is being published by Oxford University Press in the USA in October.

Eamonn is now writing a cultural history of Kabul, to which city he took his wife for their honeymoon, in 2008, during the Taliban’s resurgence in Afghanistan.

Thank you for such an interesting introductory article. I really enjoyed reading it.

I really loved this article! It’s a dream to do a trip across the Sahara desert!It fascinates me since i was a child..it’s magic!!