Antarctica, the South Pole, I doubt that any other two names have such an extreme appeal on most humans within geographical exploration and adventure. The race to reach the South Pole is continuously re-examined and re-written. But there´s so many other stories, which are kind of fallen into the darkness, which are at least as interesting, adventurous and thrilling. We have been thrilled by Long Rider President CuChullaine O´Reilly´s new evidence of meat eating horses and their time on the continent. And now, Glenn M. Stein will tell us another intriguing story, in three parts! This is the 2nd part.

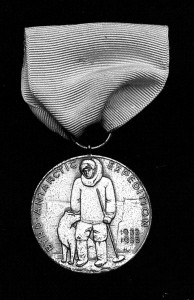

Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition Medal, 1933-1935

This morning, just 62 years ago, Byrd and his Ice Party members, including Yours Truly, sailed up the Bay to the D.C. Navy Yard. . . So wrote Dr. Alton A. Lindsey to the author on May 10, 1997 – he had turned 90 only three days before. In the early years of the Great Depression, he was at Cornell University studying for his doctorate in biology, when he interrupted this pursuit to serve as the vertebrate zoologist on the Byrd Antarctic Expedition II, 1933-1935. While the interior of the continent was canvassed by dog sled, tractor and airplane, Lindsey studied penguins, seals and other animals on the coast.

After the successful expedition, the Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition Medal, 1933-1935, was established by Act of Congress on June 2, 1936. Struck in sterling silver (oxidized, relieved and satin finish), 57 medals were issued, each having the recipient’s name impressed in sans serif capitals on the edge (I previously believed the naming to be engraved). This figure represents 56 men in the Ice Party who spent the winter night (six months) at Little America plus one to Lieutenant (JG) Robert A. J. English, U.S.N., Master of the Bear of Oakland. The medal to Admiral Byrd was issued in a named case, and this may have been a standard practice.

Hanging from a white ribbon, representing the snow and ice of Antarctica, the obverse depicts Admiral Byrd standing on ice in polar clothing; he is holding a ski pole in his left hand and a sled dog is seated on his right. In the background there are large ice formations. The dates 1933/1935 are to the right on the ice. The whole is encircled by BYRD ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION.

The reverse features a central rectangular tablet with the wording: PRESENTED TO THE OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE SECOND BYRD ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION TO EXPRESS THE VERY HIGH ADMIRATION IN WHICH THE CONGRESS AND THE AMERICAN PEOPLE HOLD THEIR HEROIC AND UNDAUNTED ACCOMPLISHMENTS FOR SCIENCE UNEQUALLED IN THE HISTORY OF POLAR EXPLORATION.

The images surrounding the tablet evidently have not been fully described in literature before now. To the left are two radio towers of Little America, to the right is the Bear of Oakland under full sail, and above what has been described as a “Ford Tri-Motor airplane” (without any landing skis); if true, this is the Floyd Bennett, salvaged from Byrd’s first expedition. Finally, below the tablet is a team of four dogs pulling a man on a sled, with ice formations in the background.

Dr. Lindsey clearly remembered the October day in 1937 when he received his medal:

When the enclosed 1937 photo was taken by a Navy photographer (otherwise now unknown), the C[ongressional] medal had been pinned upon Wm. Haines, Byrd Antarctic Expedition II meteorologist, in the private office of Navy Dept. Secretary Claude Swanson, a famed statesman of that time (seated, because too feeble to stand). [Swanson wrote the 9 1/2-page introduction to Byrd’s Discovery: The Story of The Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition] He is only pretending to pin the medal on his friend Byrd (left, with famous Admiral Leahy behind his head), and even that was an ordeal. Everyone looks so grim & unhappy because we, especially Byrd his great friend, were affected by Swanson’s condition. I am the only young man shown in this photo. . .

But Dr. Lindsey held a more important memory of an intangible reward for service in the frozen south:

The expedition ended with President F.D. Roosevelt meeting The Bear May 10, 1935 on arrival, waiting on the dock at Washington Navy Yard. I did, & still do, appreciate that handshake & conversation more than the Congressional medal. There were 56 men on the Ice Party, and the scientific staff of 10, the flyers, a few military officers (perhaps a third of the personnel of 56, received the medal by mail, late in 1937). Haines & I were living there in D.C.

In fact, the expedition formally ended six days later when the two main expedition vessels, the Bear of Oakland and Jacob Ruppert, sailed into Boston, where the participants were received at an official welcome home to Boston ceremony, hosted by the mayor.

The passing decades had not lessened memories of other former comrades on the ice. Lindsey laid down the names of the seven ‘surviving Ice Party lads’ he knew were still living in 1997:

Dr. Erwin H. Bramhall (Physicist)

Stevenson Corey (Supply Officer & Dog Driver)

Joseph Hill Junior (Tractor Driver)

Guy Hutcheson (Radio Engineer)

Alton A. Lindsey (Vertebrate Zoologist)

William S. McCormick (Autogyro Pilot)

Olin D. Stancliff (Dog Driver)

Just off the northwest tip of Canisteo Peninsula in the Amundsen Sea, the twelve Lindsey Islands are features on the map today (73º37’S, 103º18’W). Dr. Lindsey wrote that the archipelago was personally discovered by Byrd in 1940, and the U.S. Board on Geographical Names (B.G.N.) website states the islands were delineated from air photos taken during the US Navy’s Operation Highjump in December 1946. The B.G.N. named the group in January 1960.

Dr. Lindsey passed from the scene in the final days of December 1999, at the age of 92; he was believed to be the last living scientist from the Byrd Antarctic expeditions. I was tremendously grateful we shared those letters two years before, but had no inkling our exchanges would eventually lead to aid in keeping alive memories of Dr. Lindsey and the Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition.

Beyond the 1937 photograph, I had never seen a picture of Dr. Lindsey’s congressional medal, and over the years that followed, my curiosity finally prodded me into contacting the Lindsey family. During January 2009, I telephoned Louise W. Lindsey, the explorer’s daughter, and explained my association with her father. She was extremely gracious and warm, and not only offered to take photographs of the medal, but also put me in touch with her mother, Elizabeth (who had just entered her 90th year).

In the early days of February, I heard Elizabeth’s gentle and confident voice for the first time; like Louise, she was eager to help with my research and learn more about the medal’s meaning. Soon images of the medal arrived by email, and initially I winced: a naked silver disc filled the computer screen. The two top rings, ribbon, and brooch pin had all gone astray. Upon asking Elizabeth if she knew the whereabouts of these pieces, she vaguely recalled seeing them at some point in time, but doubted they could now be pinpointed. On a positive note, some of the images clearly showed the edge naming, A . A . LINDSEY.

Elizabeth’s explanation as to how the medal was passed onto her speaks of Alton Lindsey’s character. As his 90th birthday approached, his family wanted the celebration to be an extra special one, but Dr. Lindsey would not allow any presents, instead he turned the tables. He prepared several small gift boxes for some of his relatives, “with treasures from his long life of expeditions and travels. My little box contained his Byrd Antarctic Expedition II Congressional Medal,” explained Elizabeth.

Before long, my brain cells were set apace, and I put forth an earnest suggestion to Elizabeth and Louise: restore the medal. I offered to hunt up a length of ribbon and pin brooch, and their local jeweler could attach the silver rings. My idea surprised and delighted them, and so I bounded one step further: What about having a portrait photograph taken, with Elizabeth wearing the medal in honor of her husband? This idea was received with equal good cheer.

My attention now turned to the task of acquiring a ribbon and pin brooch; neither of which were readily available items. As it happened, the Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition Medal was issued with a somewhat wider ribbon than what is standard for United States medals, and consequently was fitted onto a wider pin brooch as well. A viable substitute for the first came in the form of a length of British Arctic Medal 1818-1855 ribbon, while the latter was satisfied by a pin brooch from a United States World War I Victory Medal. Not perfect matches, but very close to the originals.

In late February, I dispatched the parts to Elizabeth, along with instructions for the repair. Within two weeks, the jeweler carried out the work in a most satisfactory manner, and Elizabeth handily sewed the ribbon onto the pin brooch. On March 17, Elizabeth and Louise sat for their portrait, the medal hanging from its snow white band stood out boldly out against Elizabeth’s red lapel; Dr. Lindsey’s congressional medal had been resurrected!

US Antarctic Expedition Medal, 1939-1941

On a typically brilliant Florida afternoon in January 2009, the author strolled into the inviting surroundings of Robert L. Colombo’s home, clasping his hand for the first time. Having corresponded with Robert in October 1994 about his uncle, Louis Patrick Colombo, Robert and his sons graciously opened a window into their past.

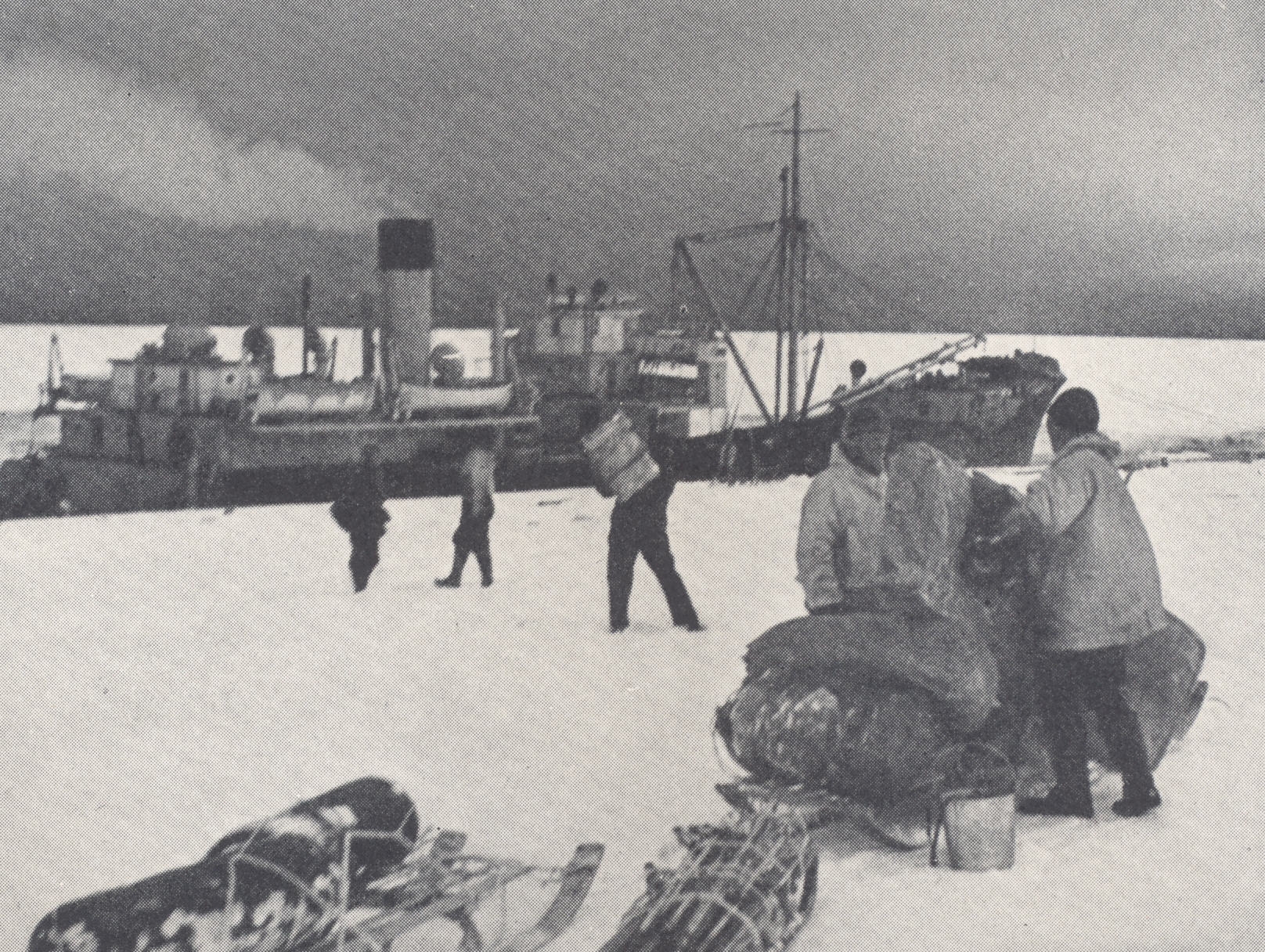

As a merchant seaman in the early 1930s, Louis Colombo was a seaman and fireman on the Jacob Ruppert on her two voyages to Antarctica during 1933-1935, and also acted as an assistant mechanic to the Ice Party (but did not winter over). In January 1934, while helping to offload supplies from the Jacob Ruppert, Colombo suffered a painful case of snowblindness; a sharp reminder of the nature of the beast.

Without being attached to the Ice Party, Colombo was not entitled to the medal for Byrd’s second expedition, but he must have felt otherwise, as a 1948 watercolor portrait in his Army uniform shows him wearing the 1933-1935 ribbon bar after that of the 1939-1941 medal. However, a portrait photograph in uniform of the same period features only the latter ribbon, and thus hints of an “official correction”. Today, the two Antarctic ribbons bars are mounted together, and grace the top of a homemade polar wall hanging several feet long.

In 1939 Congress established the U.S. Antarctic Service (U.S.A.S.), and an expedition under Byrd was sent south “to consolidate previous American exploration and to examine more closely the land in the Pacific sector.” East Base and West Base were established (with Colombo serving as a dog driver and supply man at the latter), and a whole range of scientific studies were carried out. Due to rising international tensions, both bases were evacuated by March 1941. As a footnote, this was the first expedition to the region to bring back color photographs.

Congress established the medal on Sept. 24, 1945, and three levels were again created: gold (10k gold filled (plated) over copper alloy, satin finished with burnished highlights; sterling silver (oxidized), relieved and satin finish; and bronze (red brass, oxidized dark gray, giving a pale greenish-gold color), relieved and satin finish. According to the Sotheby’s lot description of Byrd’s medal (Nov. 10, 1988), he received a unique genuine gold issue (unmarked).

In some instances, the recipient’s name was (deeply) engraved on the reverse in large and medium serifed capitals, and the author is aware of three medals (two gold and one silver) officially named in this manner: REAR ADMIRAL RICHARD E. BYRD U.S.N. (RET.), LOUIS P. COLOMBO and LIEUTENANT COMMANDER CLAY W. BAILEY U.S.N. However, the silver medal presented to George W. Gibbs Jr. (Mess Attendant 1st Class/Officers’ Cook 3rd Class, U.S.S. Bear) was issued unnamed.

Byrd’s medal was issued in a case with typewritten name attached (plus a citation with wording similar to that which appears on the medal’s reverse), and this may have been the usual practice.

Colombo passed away in October 1995 in his 84th year, but ensured the his treasured mementos from the polar adventures were eventually placed in the care of his nephew Robert. Among the two stately stuffed penguins, photographs, documents and letters, was an official letter written to Colombo at Little America III (West Base), on Sept. 6, 1940. It was from Arnold Court, Chief Meteorologist, United States Antarctic Service:

It conformance with your request, it gives me great pleasure to assure you officially that at the time we were outdoors yesterday, that is just before noon local (180th meridian) time, the actual recorded temperature of the air was – 74.0º Fahrenheit, that is, 72 degrees below zero, or 104 degrees below freezing.

At some point during the six hours previous to writing the letter, Court went on to note that the temperature actually went down to -75º, “I believe, the lowest temperature ever recorded at a permanent station in this area, or by any station of the U.S. Weather Bureau.”2

Colombo’s gold medal, stately resting in its 1950s-era plastic award case, stood out among the many varied items spread across his nephew’s dining room table. The engraved lettering on its reverse showed no discoloration whatsoever on the copper alloy, and oddly, the medal had feel of being genuine gold. It hung from a faded ribbon on its original slot brooch, and at some point, Colombo affixed to the ribbon a bronze WINTERED OVER clasp, as seen on a miniature Antarctic Service Medal (established 1960).

Also in the case was a faded ribbon bar, lapel pin and a much-worn lapel rosette. The lapel pin stirred my curiosity, as it was not the flat enamel type often encountered. In this instance, a bulbous piece of plastic was fitted over the colors.

Attention then turned to the plush dark blue pad upon which rested the above items. The pad seemed to ride a bit high in the case, creating a sixth sense that there was something more than met the eye. Gingerly, the pad was lifted to reveal an ample reward: Colombo’s Social Security card (issued during service at the Army’s Alaskan Arctic Indoctrination School), and two neatly folded pieces of paper, one of which was frail and yellowish-brown with age.

Both of the papers were letters from Byrd, relating to the issuance of the medal. Like Byrd’s writings to Harry Adams, the frail letter spoke of a different age:

NAVY DEPARTMENT

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS

WASHINGTON 25, D.C.

July 7, 1947.

Mr. Louis P. Colombo

24-31 24th St.

Astoria, L. I.

New York

As you perhaps know, Congress has awarded a medal to the members of the 1939-1941 Expedition. This medal was not finished until just before the departure of Task Force 68 [Operation Highjump, launched in August 1946, was a massive U.S. naval expedition to Antarctica]. The Secretary of the Navy decided, all of a sudden, that he wanted to give the medal to the members of the 1939-1941 Expedition who were going down on this present Expedition.

There was not time enough to notify all of the other members or to get them here. I would like to arrange for the presentation of this medal to you. What would be best for you? Any one of the following procedures could be followed:

1. We could perhaps have the Governor of the State present it to you.

2. We might have the Commandant of the Naval District you live in, or the

Commanding General of the Area give you the medal.

3. Or you might have the Secretary of the Army or Navy present it.

4. Perhaps you might prefer to have me present it to you.

You might have other ideas. Will you please write me at this office, room 4835, Navy Department, how you feel about the medal. When you write, please mark an “A” on the outside with a red “Personal”. My assistant here will then open the letter and will attempt to arrange things in accordance with your wishes.

Sincerely,

R. E. Byrd

[signed on his behalf]

R. Adm. R. E. Byrd, USN (Rtd.)

GLENN “MARTY” STEIN, FRGS, is a polar and maritime historian who was born in Miami, Florida, and raised on a barrier island south of Cape Kennedy. He has conducted research since 1975, and earned a bachelor’s degree in Public Relations and minor in History from the University of Florida.

Glenn’s writings regularly appear in journals and magazines, having published over 50 articles to date, and he has been acknowledged in several works on polar and maritime history, and medals. He is a Life Member of the American Polar Society, Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (FRGS), and member of the International Exploration Society, Orders and Medals Research Society (UK) and Life Saving Awards Research Society (UK).

In 2006, Glenn was asked to be the website polar historian for the International Polar Year 2007-2008. The invitation came as a result of applying to curate the exhibit, “The Lady Franklin Bay Arctic Expedition (1881-84) and the First International Polar Year” at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. In acknowledgement of his contributions, he received the Certificate of Appreciation from the World Meteorological Organization (Switzerland) and The International Council of Science (France). Glenn is also the designer and a recipient of the 2009 Antarctic Treaty Summit Medal.

After several years of in-depth research on HMS Investigator and her crew, Glenn is currently writing a book about the 1850-54 expedition. In 2008, his two-part article, “The Voyage of HMS Investigator (1850-54): Solving the Mysteries of the Arctic Meritorious Service and Gallantry Medals,” was published in the Orders and Medals Research Society’s Journal. The following year, Glenn was awarded the Journal Prize for this “thorough and important research into two little-known and rare Arctic awards”.

In 2011, Glenn began working with Parks Canada on its HMS Investigator/McClure’s Cache Project, contributing research and writings to the website as the project progresses.

Hi Mr. Stein:

I hope you can help me – I am trying to find information about my uncle, USN Chief Engineer Charles Meyer (Charls L. Meyer), who served aboard S. S. North Star during Admiral Richard Byrd’s Antarctic Expedition of 1939-1940; he was a crew member of the Snow Cruiser. So far my research indicates that he visited both the North and South Poles with Admiral Byrd and served with the Navy during WW II and the Korean Conflict.

If you could direct me in my research I would be very grateful.

Cathy Meyer Wiggins

Bartow, FL

I’m trying to find out which Antarctic Expedition my cousin, Robert (Bob) Reuben participated in as a correspondent.

I believe at the time of the 1939-40 exp., he was already

working for Reuters. He later parachuted @Normandy on D-Day, carrying his typewriter and 2 carrier pigeons.

Please help me if you have any info.

Thanks much, Alice Weston

Dear Ms. Weston,

I cannot find a Robert Reuben listed with the United States’ Antarctic Service Expedition, 1939-41.

However, judging from the book, “Now the News: The Story of Broadcast Journalism” (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991; pp. 185-86), Reuben was reporting on the USN Antarctic Development Program, 1946-47 (Operation High Jump).

Charls L. Meyer was my Dad’s stepfather. Our family (my cousin Betsey in Pittsburgh) has some photo albums and artifacts from his service with Admiral Byrd. I am attempting to contact Ms. Cathy Meyer Wiggins to see what we can share from Grandpa Charlie’s Naval Career.

V/R,

Mike Borland 540-720-1358

Mr. Stein,

I am extremely interested in any information you may have regarding my favorite late step-grandpa Charlie, aka Charles Meyer. I remember hearing his tales of travels with Admiral Byrd to the S. Pole as a child. It sounded surreal. I was mesmerized listening to his tales of fantastical journeys…any info you could pass on would be appreciated.

Warmest Regards,

Sandra Holloway

Here’s Meyer’s entry in “Antarctica: An Encyclopedia,” by John Stewart (2 volumes; Vol. 2, p. 1033) (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011):

“Meyer, Charles Lytton, b. 1905, Brookport, Ill., Fla. [sic], son of railroad man William Frederick Meyer and his wife Ella Lytton. When Charles was a little lad, the family moved to Dunedin, Fla., where the father got a job as a machinist, and then on to Clearwater, where he was grocery man. Charles joined the U.S. Navy, and was married to May. He was a chief machinist’s mate on the “Bear,” during the 1st half of USAS 1939-41, and coxswain on the 2nd half. He was also engineer on the Snow Cruiser.”

Snow Cruiser text and images:

http://www.pullman-museum.org/theCompany/arcticExplorer.html; http://www.joeld.net/snowcruiser/391020hat_snow.html; http://www.joeld.net/snowcruiser/391021mcn_snow.html; http://www.joeld.net/snowcruiser/391026gpt_snow.html; http://newspaperarchive.com/capital-times/1939-10-26/page-5/; http://newspaperarchive.com/indiana-evening-gazette/1939-10-10/.

Some of the USAS 1939-41 records are held in the National Archives.

Meyer’s received the USAS 1939-41 (silver issue), which was presented to him by his commanding officer sometime after the end of the Second World War.

Glenn M. Stein, FRGS

Polar & Maritime Historian

US Liaison, ITACE 2014

http://www.south2014.com

RE: CHARLS LYTTON MEYER

Trying to reach those also looking for information about my uncle. . . please email me at nativegal533@gmail.com.

Thanks!