Mangled pieces of the bridge lay visible on the river bottom. A construction worker yelled something in foreign words, which my driver translated,

“You can cross the River Omo in your four-wheel to reach the Mursi Village here in Ethiopia.”

Halfway across the swift current the Amharic word for “help” echoed through the jungle. I wondered if I should have believed the email from the agency hiring my driver, telling me to abort the Mursi trip. Due to El Nino’s harsh side effects, previous clients had to leave the area by helicopter. The worker transferred the chain from a metal bridge railing to our Land cruiser and shouted at the tractor as he coaxed it to move forward.

My driver, Girma, in broken English explained,

“We will try an opening in the jungle down the road leading to the village where the Mursi women with their five-inch clay-lip-disks live.”

Within minutes, branches, vines, and insects stuck to the car like honey. I had to give up trying to wipe the constant salty trickles blurring my vision with toilet paper, a much-needed necessity for other purposes. Intense humidity and high temperatures shut down both the air conditioner and our hopes of reaching the mysterious Mursi people. With the windows closed for protection from the clawing vines and hordes of black biting flies, we gave our attention to the dry riverbed crevices we had to maneuver. A familiar smell distracted me from my watch for problems ahead. My concerns changed course after seeing the back and side windows covered in something oily and wet. Girma ignored my questions about the smell while slowing for two men in skimpy loincloths shouldering wood handles ending with pointed metal blades. Girma tried to rationalize his reason for allowing the men to ride with us by saying,

“The men will help build temporary tree branch bridges for the tires where the jungle has given way to the flooding waters.”

The doors held tight by the wild and free jungle meant they had to climb in through the driver’s side window. Both men climbed over the front seat awkwardly, with private parts flopping about. Their hands clenched the headrests so hard their skin turned white, and I could almost hear one man’s jaw drop down to his belly with anxiety at seeing his surroundings. In and out of the window, the two men and Girma climbed in order to cut tree branches to connect the wide openings.

Minutes later, three naked men with Kalashnikovs, also called Russian AK-47 semi-automatic rifles, stood with perfect posture behind a fallen tree, stationed there to protest our passing. Adventure travel put to the test! Spirited, naked men waving rifles? Girma wrinkled his eyebrows as if to question my concern. Truckloads of these rifles cross the border from Sudan and Somalia. Locals increase their status when they carry a gun rather than a spear. My driver offered them a few coins, and they disappeared before a river stopped the vehicle once again. The Mursi people have a reputation for demanding money and food.

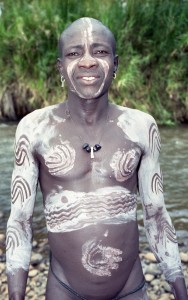

“When we reach the river close to their village, we will wait for them to visit us. Their curiosity levels match ours, plus they hope to receive some money for showing off their lip plates and painted naked bodies,” Girma said, as if he’d memorized the words before the trip. Most of the villagers materialized like whispering aliens while women pulled their loose lip-skin out and around clay disks. Shiny ebony bodies appeared from behind trees, crossing the shallow river toward us. I knew they could hear my heart beating fast and sensed my fear. My dream of crossing the boundaries of the civilized stood before me, embodied in these people, tugging at my hair, shirt pockets and camera strap. Rough pieces of tree bark had rubbed their bodies clean of hair. Intricate white designs hid the nakedness of those bodies. The sun played with the metal decorating the animal skin loincloths on the women.

A woman came close and stood still as if to offer herself for a photo. I snapped a few pictures. She took the lip plate out of her lip, offered it to me and held up her fingers. Girma said she wanted a ten-birr note ($.80). I knew I had to pay for every photograph when they increased the number of fingers held up which each click. The tribes understood the reason for my presence. If I can reward these people for giving me their time while continuing their traditional ways, perhaps in some small way I will contribute to the preservation of their culture. The line gets crossed with fairness versus the tribes taking advantage due to some tourists tossing hundred-birr notes ($8) at them for a couple of photos. Tribals soon learn the value of money and expect the next visitor to pay the same. When the tourists say no, situations happen, like the three naked men appearing. An argument started between two women and a man. Apparently, the husband thought he might miss some payment since I took a photo of another woman and not his wife. After a half hour of trying to communicate with my driver and watching my photography antics, the chief asked Girma for the equivalent of twenty dollars. A group of men circled the car waving spears or rifles. Girma reached for two boxes of crackers to pass out and, with caution, opened the car door. I followed his actions. A live encounter with the Mursi tribe could provide a frightening experience not worth the effort of getting there. Leaving under this kind of stress caused a sensation of needles pricking my arms and face. Burning salty sweat kept me from seeing the real aggression in their eyes. The driver ignored the crowd around the vehicle while creeping forward. Dead ahead, the three naked men, now wearing loincloths, pointed the guns in our direction while standing again behind another dead tree. They caught the birr, or Ethiopian currency, in midair as Girma tossed it toward them and proceeded around the dead tree. The driver explained that last week they had killed a park scout! We searched for the dip in the tree canopy, evidence of the previous tree felling.

A rough dirt road never looked so good until we left the car for some fresh air. With tears in his eyes, my young driver circled the clawed, dented and diesel fuel-covered car. The jungle growth had worked hard to try to keep the vehicle from entering its playground. Headlights, taillights, bumpers, and trim pieces looked like an angry weightlifter had slammed his heaviest weights at the vehicle. Thorn bushes fought with broken branches, competing for the challenge of leaving their imprint of black horizontal stripes across every door. All of the five-gallon diesel fuel containers remained tied to the misshapen luggage rack, crushed to a fourth of their original size. Three weeks of fuel washed the car while we dealt with men with guns.

I never thought much about what might have happened to us, nor at the time did I worry when I saw the almost ferocious look on the men’s faces as they gathered around the 4X4 chanting for money. Traveling to meet indigenous societies requires a vast amount of trust and patience for one’s driver and all of humankind. If some gypsy could have predicted that situation beforehand, perhaps I would have thought twice about trying to find the Mursi.

Jackie Chase travels the world meeting people from exotic cultures reaching for new challenges along the way. Even as a Midwestern housewife she felt compelled to share her adventurous nature with her four children. Jackie is more of a writer who travels versus a travel writer, sharing secrets from unique people whose lives help us all in the way we look at the world. Read more at http://culturesoftheworld.com/blog/