South Pole Ponies part 2

The Forgotten Story of Antarctica’s Meat-Eating Horses

by

CuChullaine O’Reilly FRGS

Unlikely Equestrian Allies

Modern folklore delights in focusing on the intense rivalry which existed between the Norwegians, led by Roald Amundsen, and the English, led by Captain Robert Scott, with the former relying on dogs to pull their sleds, while the latter obstinately preferred to “man haul” their equipment across the ice. That story sold reams of newspapers in its day and continues to fuel a lucrative niche publishing industry. Nevertheless, this is an erroneous simplification of events perpetrated by pedestrians, one which overlooks an astonishing series of under reported equestrian event.

Disregarded is the fact that this was not a two-horse race between two bitter nationalistic foes determined to champion different methods of travel. Prior to Scott’s departure for Antarctica, Germany and England were still on such friendly terms that it was agreed their explorers would simultaneously use horses, some of whom it was later discovered were meat-eaters, to try and meet each other in Antarctica.

This decision was brought about in 1912, when Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II authorized explorer Wilhelm Filchner to travel to the South Pole. The young German had already made successful explorations across Central Asia, most notably when he rode from Baku to the Pamir Mountains in the late 19th century.

Having received his nation’s commission to explore the southernmost continent, Filchner journeyed to London in search of first-hand knowledge regarding polar travel. Here he was befriended by Captain Robert Scott and Sir Ernest Shackleton, both of whom encouraged and helped the amateur Polar explorer.

After a series of meetings it was agreed that somewhere in the vast white expanse of Antarctica, the Germans, led by Filchner, would locate the British team, led by Captain Scott, whereupon the two nations would exchange personnel before retiring to their respective camps on either side of the continent. Both expeditions were to use horses, in addition to sled dogs. The British also relied upon motor-driven tractors, and in extremis, man hauling.

Neither team leader realized at the time that both their expeditions would rely on meat-eating equines in this effort. Nor was it known that the Norwegians were even planning on being anywhere near Antarctica, as Amundsen had announced he was trying instead for the North Pole. Therefore, if events had gone as planned, German and English equestrian travellers would have met as friends somewhere in the vast frozen continent.

Sadly, this did not occur. Filchner’s role was air-brushed out of popular history. Germany’s involvement was ignored, as it distracted from the unexpected rivalry brought about by Norway’s explorer showing up to thwart Scott’s role. Nor were the equestrian events, either before or after Scott’s death, fully understood or documented.

To begin with, a profitable modern industry has arisen which delights in highlighting the personal and professional dispute which had arisen between Scott and his former lieutenant, Shackleton. All too often it is forgotten that on their first expedition to Antarctica, Scott had saved Shackleton’s life.

Consequently, while they were indeed rivals for the Pole, what the opponents of either camp neglect to appreciate is that both men maintained an abiding respect for each other’s talents.

Moreover, thanks to Filchner’s unexpected appearance in London, a significant moment in equestrian travel history soon occurred, when Scott was preparing to leave England’s capital. His slow ship and her crew had already departed for Antarctica. Having concluded last-minute fund-raising, Scott was now taking a train to the coast. There he would board a fast sailing passenger liner bound for New Zealand, where he would rendezvous with his expedition.

When Scott boarded the train, Shackleton and Filchner were waiting to bid their fellow explorer farewell.

Thus, Shackleton and Scott, the two former expedition comrades, shared a poignant final meeting. Any residual antagonism which existed between the Irish and English explorers was temporarily laid to rest, as the two experienced polar travellers expressed what were unknowingly going to be their last farewells.

Ironically, as the train pulled out of the station, Scott’s final words were aimed not at Shackleton, with whom he had shared many desperate adventures, but at his fellow equestrian explorer, Wilhelm Filchner.

“See you at the South Pole,” Scott yelled to Filchner, as the train pulled away from the London station.

As Scott departed, none of the three explorers could have realized that this was their last meeting. The lure of the South Pole would soon kill Scott. It would then seriously imperil the lives of Filchner, Shackleton and all the men involved in both their own expeditions.

South Pole Ponies

What is seldom remembered today is that like Shackleton and Jackson before them, Filchner and Scott were also using Siberian and Manchurian horses to assist them in their push to the frozen end of the Earth.

Upon departing from London, Filchner returned to Germany, convinced that he and Scott were in agreement on an extraordinary plan which incorporated the themes of international cooperation, scientific advancement and horses. There had been no hint of commercial, national nor personal competition.

Filchner never met Scott. Paradoxically, he encountered his nemesis instead.

After setting sail for Antarctica with his ship and crew, the German stopped at the harbour of Buenos Aires. There Filchner chanced upon the Fram. This was the Norwegian ship captained by that country’s famous polar explorer, Roald Amundsen. Unknown to Scott, this Norwegian rival had unexpectedly launched what was to become a nationalistic race to the South Pole. Thus, before Scott had any clue as to what was afoot, the Germans realized that a three way national effort was now under way.

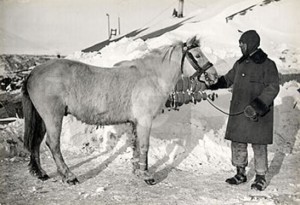

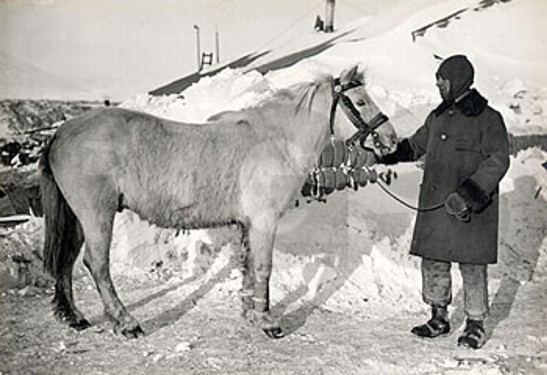

The Fram, with Amundsen’s large contingent of sled dogs, sailed first. Afterwards, Filchner and his German expeditionary force also departed for Antarctica, bound for the opposite side of the continent than that which the Norwegian and British expeditions had chosen. Filchner landed on Antarctica, where he unloaded the horses and dogs he had brought for his team’s push to the Pole. Unfortunately, the ice on which he set up camp was unstable and the expedition was unable to proceed.

Nevertheless, in stark contrast to modern dogma, which insists that it was a race to the Pole that pitted British man-haulers against more competent Norwegian dog-sledders, there were in fact two equestrian expeditions, camped on opposite sides of Antarctica, at the same time, and they had planned to meet !

Like Scott, prior to his departure Filchner had purchased Manchurian horses to explore Antarctica. Upon arriving, he was surprised to learn that because the dogs viewed the ship as a home, they had to be separated by force from the ship, unlike the horses who eagerly went ashore and “when they felt terra firma under their hooves; they bit, kicked and pranced from high spirits and joie-de-vivre.”

Filchner also remarked on the ease which his horses pulled sledges weighing 1,200 pounds.

“As draft animals the ponies achieved miracles.”

Though the Germans were unable to either reach the South Pole, or locate Scott, nevertheless they enthusiastically rode their horses in Antarctica. One German, the Historical Long Rider, Alfred Kling, regularly explored on a Manchurian horse named Moritz. Another of these horses, Stasi, eagerly ate dried fish and raw seal-meat.

Captain Scott – Equestrian Explorer

While Filchner had problems, Scott was facing a disaster on the other side of the continent.

Unlike Jackson and Shackleton, Scott took a different view on equine nutrition. He brought none of the high-energy Maujee ration for his horses, deciding instead to feed them compressed fodder made of wheat. He also gave the horses hot bran mash with either oats or oilcake on alternate days.

Despite their traditional diet of hay, oats, bran and oil cake, the equestrian report compiled after the English expedition concluded, “The nutritive value was insufficient under the conditions of sledging and the ponies became very weak and lost flesh markedly.”

Regardless of his well-meaning efforts, Scott’s horses “lost weight until they were just skin and bone.”

Nevertheless, even though they lacked the tasty Maujee ration, eyewitnesses recorded that at least one of Scott’s horses was an avid meat-eater.

“One of our ponies, Snippets, would eat blubber and so far as I know it agreed with him,” Cherry-Garrard wrote.

Cherry-Garrard was later part of the rescue party that found the frozen bodies of Scott and two of the men who had accompanied him on the final push to the Pole. Once again, the equestrian portion of that tale has been almost entirely deleted from popular cultural records.

Prior to his fatal departure to the South Pole, Scott had written to the British army authorities in India asking them to authorize the use of mules which had been specially trained in the Himalayan Mountains. In accordance with that request, seven of these carefully trained mules travelled from India, down to New Zealand, and on to Antarctica. Accompanying them was special equipment based on ideas formulated in the Tibetan Himalayas. This included equine snow shoes and tinted snow goggles.

These valuable animals accompanied the rescue party, led by the surgeon Dr. Edward Atkinson, which set out to locate Scott and his missing men. The snow shoes sent from India worked so well that the mules were able to cross crevasses with them.

In a special equestrian report later authored by Atkinson, he stated that “the mules covered nearly 400 miles and were in such good fettle they could have done it again…..They were obviously stronger and better trained than the ponies and would have done even better than the ponies and pulled longer distances.”

(Notes on the Ponies and Mules used during the Terra Nova expedition of 1910-12 by E.L. Atkinson)

Nevertheless, Atkinson noted that when it came time for the English expedition to leave Antarctica, the perfectly healthy mules were killed rather than returning them to either New Zealand or India.

Equestrian Antagonism

There is still an entrenched dog-friendly view of polar history which has been written by those lacking any appreciation or understanding of equestrian history.

Though three Antarctic expeditions used meat-eating horses, recent books have continued to denigrate and erase this portion of equestrian history. One volume states, “No horse that set foot on Antarctic ground ever returned.”

(Antarctic Destinies by Stephanie Barczewski, published by Continuum Books, London, 2007.)

This statement is misleading, if not inaccurate, because even though the German expedition was unable to proceed off the ice and onto terra firma, upon the completion of his journey to Antarctica German Long Rider Wilhelm Filchner did indeed save all of his horses. He released the still healthy Manchurian horses on South Georgia Island, allowing them to run wild on the Hestesletten (Horse Plain). The descendants of these horses remained on the island for decades.

Another striking example of this antagonistic philosophy is provided by The Antarctic Dictionary, A complete guide to Antarctic English. Authored by Bernadette Hince, and published in 2000 by CSIRO Publishing, this so-called “complete guide” has no mention of horses, ponies or mules. There are a total of 394 pages, most of which consist of quotations from various books on the subject, yet the author has eliminated equestrian events, and any reference to meat-eating horses, out of her dictionary.

With the death of Captain Scott, and the failure by the Germans to reach the South Pole, the curtain drew down on the role of meat-eating horses in Polar exploration history; nevertheless these astonishing episodes raise intriguing questions.

What would have happened had Scott and Filchner managed to join up their expeditions?

For example, Scott’s equestrian expert, Captain Titus Oates, was a noted xenophobe who could barely manage to be civil to the English expedition’s sole foreigner, an easy-going Norwegian. Consequently, the idea of Oates having to interact with the Germans, or be transferred under Filchner’s command, will unsettle traditional Antarctic dogma.

Deadly Equines reveals that Polar expeditions which used horses equipped with equine snowshoes, and trained to eat meat, could have travelled to the South Pole before dog sleds reached that elusive goal.

If you have additional personal or historical evidence, please contact CuChullaine O’Reilly at

longriders@thelongridersguild.com

To learn more about the “Deadly Equines” research project visit –http://www.lrgaf.org/deadly_equines.htm

To participate in the international discussion regarding “Deadly Equines” visit –

To order the book visit – http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/deadly-equines-cuchullaine-oreilly/1104580837?ean=9781590480038&itm=1&

One comment