A friend once told me of a boat trip to Greenland, the boats crewed by a mix of climbers and sailers. The trip was tough, with big seas and storms, and as soon as the boat docked all the climbers scrambled up and onto dry land. The sailers where different, they were in no rush to leave. He told me that he realised, just as they did, that on the water these men where kings, in control of their lives. On land they were just men, each in their own way failures, failed marriages, failed finances, failing livers. Why would they ever want to step back into the real word?

A few weeks ago I was sat in my car on the long journey North from Sheffield to Scotland, heading up to do gigs in Perth, Edinburgh, Inverness and Aberdeen. I don’t like spending a lot of time by myself these days, as I find my mind tends to mull far too much over my life, the resulting conclusions often far from positive.

A few days before I’d had to go to Belfast to get an I-Visa from the US embassy, needed in order to work on the Sports Relief climb in Zion with Alex Jones. To be honest, having just got back from Antartica, and straight into a tour, it was the last thing I wanted to do. Me and Karen had broken up, and just felt overwhelmed by everything, and secretly hoped that my visa would be refused so I could get my head in some kind of order. The BBC had bought my plane ticket, and I just had to get to get from Sheffield to Manchester airport, so just got the bus down with plenty of time (due to my long history of missing flights). At Sheffield train station, while waiting to get my ticket, someone came up and told me how much they’d enjoyed ‘Cold Wars’ and that it had really helped them feel better about having a ‘normal life’ – that it had made him see that a life of climbing was perhaps not quite as amazing is it seems. I always feel embarrassed when people say things like this, but recently I have begun to draw some comfort from the effect my writing has had on peoples lives, that I shouldn’t measure my worth on my bank balance. At Buxton another person had told me Psychovertical had helped them deal with depression, and most days I get an email about how much these books have meant to people I’ve never met. Saying thanks, I went to the machine to buy my ticket, only for it to be declined, then found on checking my bank account that I only had £10 left to spend. I stood there unsure what to do, knowing if I fucked this up, and didn’t get a visa it would make a huge mess to sort out for all the people who’d been involved in the project (as ever I was 100% committed to something, only to loose interest when it came down to doing it). In a instant I had an idea, in fact it was the only one, and found the guy who’d told me he’d liked my book in WH Smiths, and guilty asked if he could lend me £35. Needles to say I think this only confirmed his belief that being a professional climber (one who’d just come off a trip that had cost a couple of hundred grand) was not all it was cracked up to be.

And so sat in my car, driving North, I begun to wonder where I’d gone wrong in my life. Sure there are many things that are right, stuff that people always point out, like lots of amazing climbs and trips, books and shows that mean something to people, but sometimes I feel like the king of experiences sat on a throne of ashes. Being negative in a negative frame of mind I began to make a list of where I’d gone wrong, and came to the conclusion that I had just been far to concerned about being a good person in the eyes of strangers, thinking too much about what people thought, helping others instead of helping myself, not focused on making money from climbing. I had this terrible image of people being ballast, and that they’d dragged me down. I had this image that a success you really need to be a bastard, and the bigger the bastard, the more success you’d have.

I read how the Wright brothers, when arguing about a problem, would always switch sides to check if there reasoning was correct, so having come to this depressing conclusion, I tried to see it from the other side. When I thought harder about it, it was easy to see that I had blown so many chances by being unable to compromise or play the game, that throughout my life I just self sabotaged every opportunity that came my way (always saying or doing the thing that hurt me the most). It was easy to see that life had been more than fair and I had no one to blame, that I had been sponsored by Berghaus and Patagonia, and had made more money than in any job I’d had, but had chosen to walk away, because I feared the pressure would lead to me killing myself in some stunt (I was also probably always afraid they’d drop me, and couldn’t deal with the rejection). I’d had opportunities to make TV programs, or work with companies that would see me financially secure, but I’d turned them down, as I worried what other people would say. The successes I had had where also down to this uncompromising focus, that once I set myself a goal (writing a book, climbing a new route in Antartica) nothing could stop me, that I would try and make it happen no matter what the cost (money, relationships, even life itself). I’m an opportunist, and always believed something else would come along, that financial success would come without me having to try and make it happen, but in the end I had always subconsciously fucked it up. But when you’re 42, with no partner, a broken heart, no savings, nowhere to live, just a knackered car and mountain of climbing gear, you do begin to worry that you’ve made some dreadful mistakes, and would happily swap all the riches people think you have, for something more material.

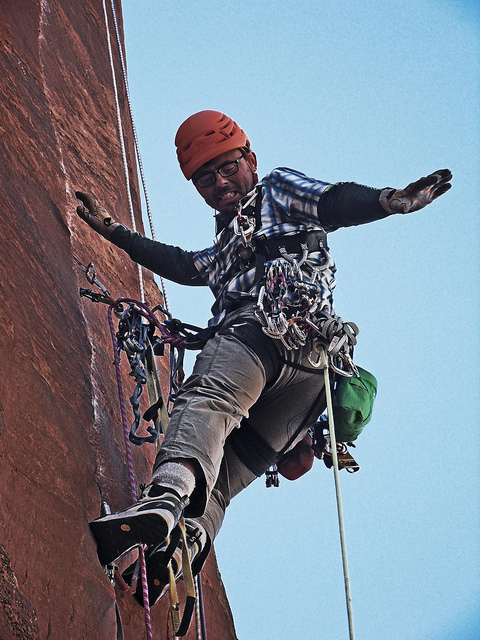

But I did make it to Belfast (waking from the City Airport in the usual Belfast rain), and did get my I-Visa and so made it to Zion with Alex. You can watch the doc about the climb on BBC iplayer, and check out the pics on my flickr page, but needles to say it was pretty epic (Sports Relief had originally rang me to ask if a celeb could climb a wall, as they’d seen me climb El Cap with a 13 year old, to which I’d replied “Ella is no ordinary 13 year old”). Alex was amazing for a non climber, and what fear you saw on TV was only 50% of the real fear at the start, but she knuckled down, and with the support of some amazing people (Paul Tattersal, Brian Hall, Ben Pritchard and Rory Gregory) she made it to the top.

On the last night on the wall we heard that Alex had raised nearly a million pounds (at the moment it’s nearly 1.5 million), and seeing her face on the summit, well that all made it worth while.

On the summit there was a real circus, but within about 20 minutes they were all gone, leaving just the climbers to sort out the kit and haul up the bags. Our the kit up, we all sat in the sand and did what I love best about a climb, we just sat if if we had nowhere to go and just talked about climbing and climbers, putting off going down to the real world.

Andy Kirkpatrick was once described by The US magazine Climbing as a climber with a “strange penchant for the long, the cold and the difficult”, with a reputation “for seeking out routes where the danger is real, and the return is questionable, pushing himself on some of the hardest walls and faces in the Alps and beyond, sometimes with partners and sometimes alone.” More succinctly, Metro magazine claims that he “makes Ray Mears look like Paris Hilton”. Read more on his homepage at http://www.andy-kirkpatrick.com/